Digital skills are critical to achieving universal and meaningful connectivity (UMC), ensuring that individuals can fully harness digital benefits and mitigate associated risks. Limited digital skills pose a major barrier to closing connectivity gaps, risking the reinforcement of existing inequalities. Digital skills are addressed under two UMC dimensions: Digital Skills (encompassing information/data literacy, communication/collaboration, digital content creation, and problem solving) and Safety/Security (focused on safety practices). This importance is recognized internationally, notably in the Global Digital Compact (GDC) and SDG 4.

ICT skills are measured through self-reported activities (20 activities categorized into five skill areas) carried out on digital devices in the last three months, a methodology aligned with the EU Digital Competence Framework for Citizens (DigComp). Individuals are categorized as having at least basic digital skills if they perform at least one relevant activity in a given area, and above basic skills if they perform two or more activities. Overall skills require meeting the threshold across all five skill areas.

Activities used to calculate ICT skills, by skill area

Source: ITU

Analysis of available data, though limited, reveals significant trends and disparities. Gender divides in ICT skills among Internet users are not apparent in countries reporting data, suggesting that where women are connected, their skill levels tend to match men’s. However, stark differences emerge in the urban-rural divide among Internet users. While communication and collaboration skills are nearly universal for both groups, rural users lag significantly in digital content creation and problem solving.

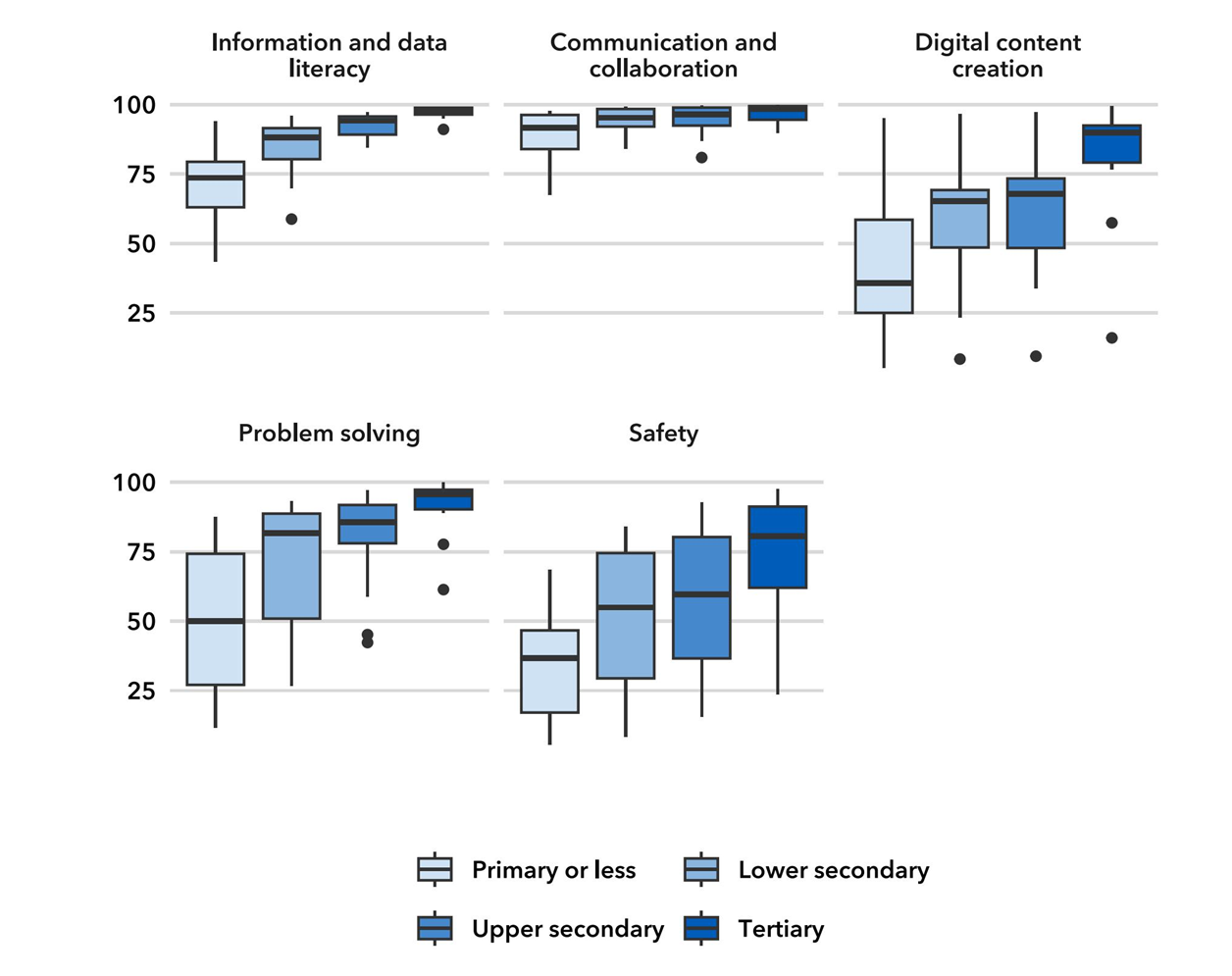

The strongest predictor of digital skills is educational attainment. Internet users with tertiary education show high proficiency across most skill areas. However, divides in skills like digital content creation and problem solving are substantial between the most and least educated. In the essential area of online safety, low skill levels among those with lower levels of education indicate that they are often more vulnerable to scams and digital hoaxes.

Share of Internet users with at least basic ICT skills by skill area and level of education attained, 2024 or latest year

Note: Data for 19 countries with available data for 2021 or more recent data. Primary or less refers to ISCED 0-1, Lower secondary to ISCED 2, Upper secondary to ISCED 3-4, Tertiary to ISCED 5+. Bars indicate the 25th, median and 75th percentile of all country values. Bottom and top lines indicate the minimum and maximum values (excluding outliers). Outliers are marked with a dot.

Source: ITU

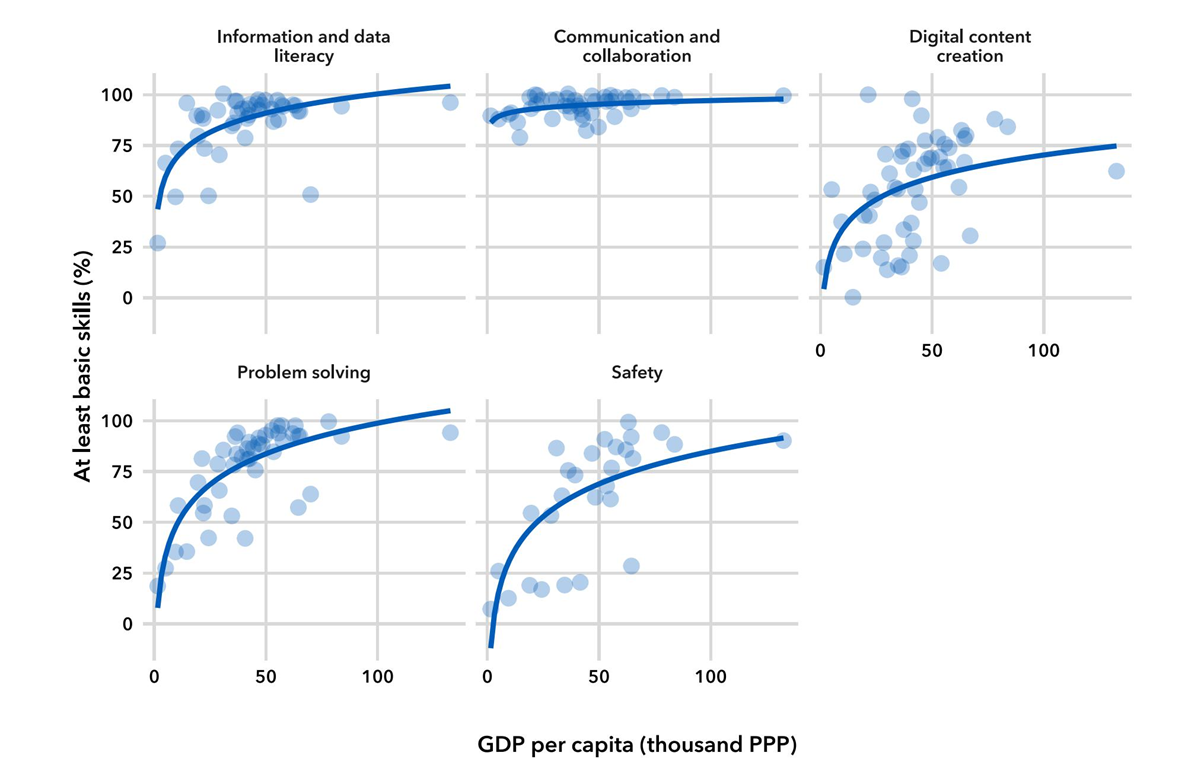

Data on ICT skill levels highlight substantial variation across countries and skill areas. The relationship between national income (GDP per capita) and the digital skills of Internet users is weak for communication and collaboration skills – such skills are near-universal regardless of a country’s income level. For other skill areas, the compounding nature of digital divides is clearer: low-income countries often have both lower Internet penetration and lower ICT skills among those who are connected.

Share of Internet users with at least basic ICT skills and GDP per capita by skill area, 2024 or latest year

Note: Includes countries with data for 2021 or more recent data. GDP per capita refers to thousand 2021 constant price PPP dollars

Source: ITU; International Monetary Fund (IMF) for GDP per capita.

To address these gaps, governments need comprehensive, evidence-based national digital skills strategies that set concrete targets across all skill areas. Programmes must be tailored and targeted to all population segments, including older individuals, women and girls, and rural populations. Crucially, strengthening digital safety skills must be a priority due to the urgency of cyber-enabled crime and misinformation. The measurement of ICT skills must be integrated into national development plans, with National Statistical Offices (NSOs) systematically conducting household surveys using international standards updated by groups like the ITU Expert Group on ICT Household Indicators (EGH).