The financial attractiveness of many of the investment in the infrastructure sector is either low, too far into the future or too risky. For illustration, investment in one 4G base station in a rural setting may cost USD 75,000 with annual operating costs of USD 10,000. To make this business case viable, the base station would need to drive at least 500 new customers to generate a 7 year pay-back. For rural areas realizing this uptake is unrealistic without additional actions on making the devices and the broadband plans affordable, skill sets, local content and stimulating demand for broadband in the community. The above example also shows the importance of holistic action across all focus areas to ensure such investments become attractive as it helps drive the business case for private investors.

Key issues: Attractiveness of business case/project preparation

Project preparation and viability is a complex process involving large teams and multiple stakeholders (ministries like ICT, Finance etc.), private/public entities, banks/financial institutes as well as multitude of interfaces between different functional entities. It is of paramount importance that a thorough business case analysis is conducted including the sensitivity analysis on key risks and potential economic scenarios.

Potential interventions: Project preparation

- Rigorous project preparation: team and leadership, governance structure with clear roles and responsibilities

- Bankable feasibility study: technical scope, sustainability requirements, adequacy with the economic, political and social environment, commercial attractiveness

- Risk allocation and regulation: incentives, risk mitigation and safeguards

Key issue: Political and regulatory risks

Political and regulatory risk is a categorization that includes those risks arising from individual political and regulatory decisions that affect an infrastructure project or an existing asset. In particular, the approach distinguishes political and regulatory risk affecting specific projects and those affecting the whole economy.

During the different stages of a project’s life cycle, infrastructure projects are exposed to very different types of political & regulatory risk. Among the risks are, for example: during the planning and construction phase – delayed construction permits, and community opposition; during the operating phase – changes to various asset-specific regulations, and outright expropriation; towards the end of a contract – the non-renewal of licences and tightened decommissioning requirements.

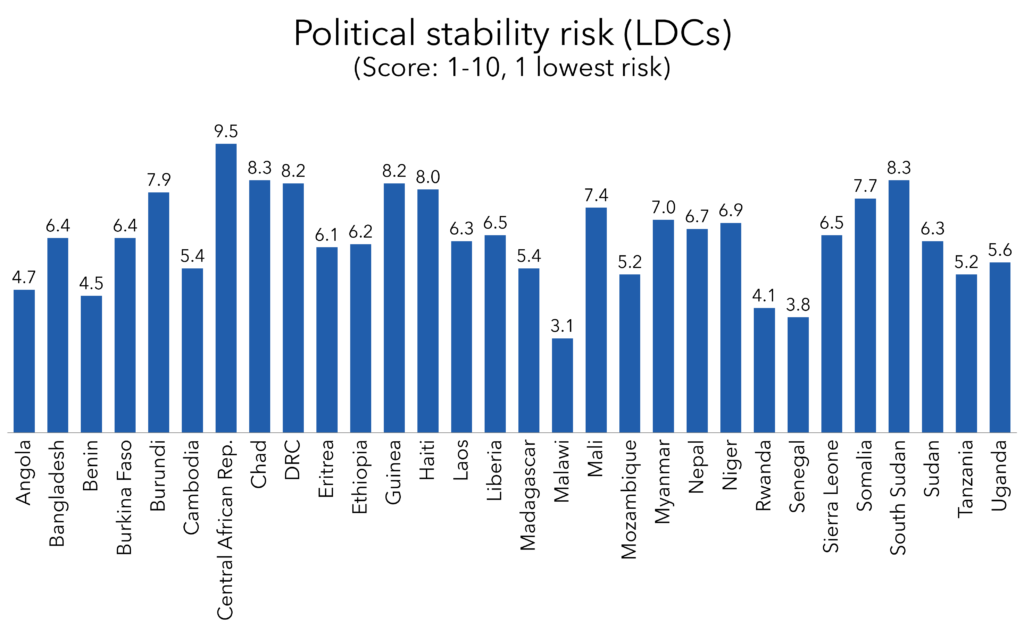

As Figure 35 shows, most of the LDC countries have a very high-risk score (lower the score, less the risk). The risks can be categorized as follows:

- Specific project related: Change of scope, Permit and environmental risks, Community risks

- Sector or whole economy: Change of regulation, taxation, Currency related, Corruption/market-distortion risks

- Demand volatility: Linked to income volatility in many of the developing countries or LDC

Potential interventions: Risk management and mitigation

- Optimization of regulatory levies and sector specific taxes: ICT infrastructure is an essential utility and core pillar on which digital technology rides. Governments should explore optimizing levies and taxes to exploit the public good and multiplier effect of telecommunication networks.

- Infrastructure regulation and contracts: Ensuring that any changes to sector rules are as predictable as possible is important for maintaining a balance between public and private interests over time.

- General stability of laws and regulation: Investors look for reassurances to sector specific and general laws

- International commitments: To reduce uncertainty about national political decisions, governments can commit to international treaties. The longer an investment is committed to, the more important investment protection becomes – which is why international investment agreements (IIAs) are of such relevance for infrastructure assets.

- Sustainability and environmental policy: Define investment policies considering the standards in force in terms of sustainability and respect for the environment.

- Private sector interaction with public sector: To mitigate political & regulatory risk, private companies should make a conscious effort to facilitate constructive interaction with the public sector.

- Demand volatility: One approach could be to follow a multi-country portfolio approach like targeting regional trading blocks whose existing political and economic cohesion can help in projects and fund disbursal. These blocks could also give a higher priority to the funding of the regional broadband connectivity and accessibility to advance their cohesive agenda.

Key issue: Capacity development

At each phase of the life cycle, considerable skilled manpower is needed – for planning, engineering, legal, financial, economic, or administrative work. Many governments, particularly local or regional governments in low-income countries, simply do not have enough of that vital resource. But even in high-income countries where PPP skills may be available in central units of government, civil servants in the agencies implementing PPPs will often lack the necessary expertise – in particular, they might lack skills that may be non-essential in traditional public procurement but that are crucial to PPPs (such as financial, legal, and transaction skills). All too often, the civil servants assigned to plan and manage a PPP are inexperienced and untrained for the role. Governments would do well to introduce dedicated training programmes or to upgrade them if they already exist.

Potential interventions: Capacity building

Individual and institutional capacity building need to complement each other.

- Country-level capacity building: Broad government capacity building strategy

- Institutional capacity building: Standardization of guidelines and tools, data collection and analysis/evaluations

- Individual capacity building: Training and knowledge sharing, Talent, and leadership development.

Commit to a pledge on our Pledging Platform here. See guidelines on how to make your pledge in Pledging for Universal Meaningful Connectivity and examples of potential P2C pledges here

Footnotes

[153] The BCG analysis is based on World Bank and Oxford Economics data.

[154] Oxford Economics. (2020). Economics and Political Risk Evaluator.