B.3 Assessing the fund

Reviewing the effectiveness of funds requires policy-makers, regulators, the industry, community stakeholders and fund managers to consider how well funds have functioned and assess levels of trust engendered by the use of those funds. These two factors will be critical if the fund is to evolve to USAF 2.0, which is what is required to extend broadband and increase digitalization.

B.3.1 Measuring in context

In assessing the current USAF impact, policy-makers, regulators and fund administrators responsible for strategy implementation should first consider what instruments the assessment is being measured against and what role the USAF has played in supporting these instruments.

Instrument: | National broadband strategy and plan / digital agenda / roadmap cross sectoral national digital strategies which support UAS efforts and which the UAS strategy supports. |

| Measure: | What targets were set and what role has USAF played in meeting it? |

| Instrument: | Market gap analysis, baseline data, scenario planning and forecasting and/or mapping . |

| Measure: | What targets were set and what role has USAF played in meeting it? |

| Instrument: | Technology analysis and plan. |

| Measure: | What targets were set and what role has USAF played in meeting these? The mix of access technologies? Were any changes made during the course of the strategy? |

| Instrument: | Budget |

| Measure: | USAF performance against budget. |

This initial check assumes that research, assessments and budgets (instruments) were prepared at the outset, and that this supported the work of the universal access and service fund. In the absence of these instruments, since it is difficult to go back in time to reproduce them, it is important for policy-makers and fund administrators to correct the situation and make sure that these instruments are incorporated into the planning when either:

- the UAS policy or UAS strategy is being reviewed, for example if the period of the strategic implementation plan has expired and a new plan is being developed, or if a country is in the middle of the strategic planning cycle; or

- the performance of the UAS fund is being reviewed; or

- the performance of the ministry or regulator is being reviewed.

B.3.2 Performance assessment

Over the years, UAS funds have been criticised for being ineffective and inefficient. Stakeholders have gone as far as saying that funds have failed. Some of this criticism is perception, some is reality. In order to establish the facts, in an evidence-based manner, an assessment or audit of the fund must be conducted. This may be initiated by the policy-maker or the fund administrator.

From a perception perspective, the most common factors mentioned to support the argument in favour of the “failure” of UAS funds s and the policies and strategies that support them have been highlighted by stakeholders such as the GSMA and include:

- levies are set without any analysis of the subsidy levels needed;

- many funds suffer from low human capacity and poor or inefficient administration;

- programmes for the deployment of infrastructure and services often do not take into account the whole ecosystem or the total cost of ownership/ participation, i.e. they neglect issues related to training and education, maintenance, power sources and other sustainability concerns – often this is linked to narrow and/or outdated fund mandates;

- transparency for most funds is inadequate – for example, with no set targets, no audits, no periodic reports or published;

- funds are affected by political interference; and

- underlying legal frameworks tend to be poorly-conceived and thus affected by the lack of technological neutrality, lack of service-flexibility, excessively bureaucratic structure or insufficient oversight.

Through an assessment of the performance of a UAS fund, an audit of the fund will give an objective and evidence-based assessment of the grounds for allegations of failure. The solution will not always be to reform, as this will depend on the institutional framework and design, issues that are discussed further in this section. If funds are not performing, it might be necessary either to dissolve the fund and make a decision on how to use money already collected or to pause the fund, put it in “fund rescue” and place a temporary moratorium on the collection of further funds until the appropriate institutional arrangements can be made to ensure its effectiveness.

Sources of funding

Principle: Analysis of UAS gaps should indicate the level of subsidy needed

Historically, contributions to UAS funds range from 0.2 per cent (e.g. South Africa) to 6 per cent (e.g. Malaysia), with an average of 1-2 per cent of turnover in most countries. The requirement to pay this levy has been set in the legislation or regulations. In most countries, despite changes in operator revenue and profitability, the introduction of new players and changes in market size, the levies have not changed since inception, creating the impression that the levies bear no relation to sector need or identified UAS gaps.

In order to address the perception in many countries that levies are set without any analysis of the subsidy levels needed, an UAS needs and gaps analysis should be carried out. This will be critical in setting levies going forward and to guard against ‘over-collection’ or ‘under-collection.’

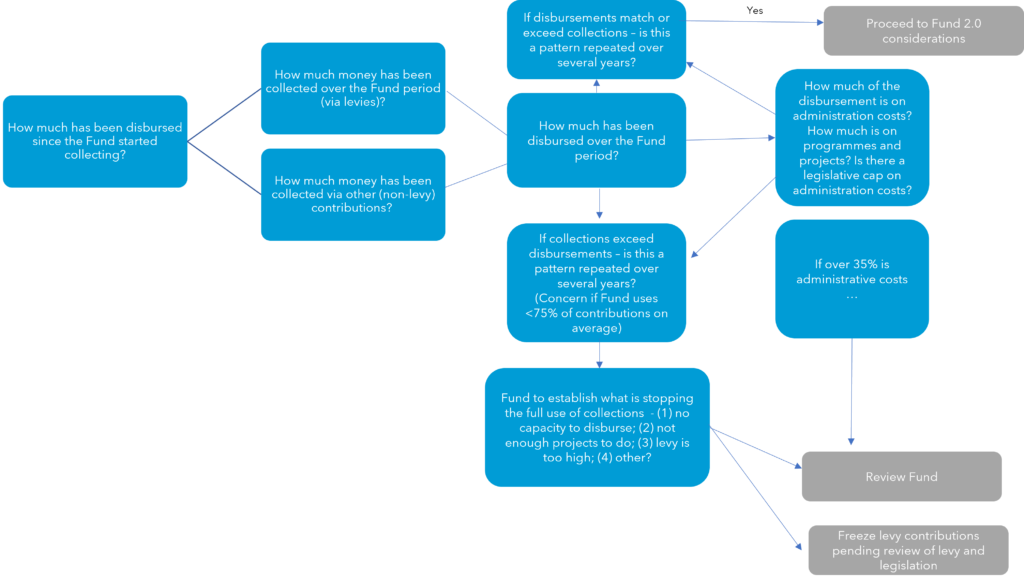

In order to address historical concerns regarding monies already collected, any audit of the fund should include aspects that directly address the ‘over-collection’ perception. Fund administrators and managers should assess collection versus disbursements for the purpose of proceeding to USAF 2.0(assuming other criteria are met although there is no single model for any future USAF 2.0); or whether it requires a review and possibly a simultaneous pause to the collection of levies (See figure below, Collection vs Disbursement).

Collection vs. Disbursment

As a second part of the audit, in order to understand how underspending or overspending may have occurred it is important that the analysis confirms:

- How is the fund allocated?

- Do funds go directly to the fund or to a national treasury??

- If the latter, does the fund have to apply to allocate funds? Is the levy and the amount the fund receives the same?

- Can the fund be used for UAS?

- Is the fund ring-fenced and can it still be used for UAS projects?

- Is there a way to separate contributions made to date and those made after the review and treat them differently?

In some countries, money collected via operator levies is paid into the national treasury and the fund must apply to allocate funds. There is no guarantee that all funds collected from operators, and other eligible sources, will be allocated by the fund and therefore the use of contributions is not fully controlled by the fund. Such practices contribute to the argument that the USAF levy is actually similar to a general tax. Furthermore, in such scenarios, the freezing of the levy will have an impact on future contributions, but it is unlikely that they can be reimbursed.

Understanding fund expenses

Administration expenses

Administrative expenses apply to operations and management of the programme or project.For example, the costs of general meetings (UAS fund board, oversight committees), legal services, auditing, accounting and finance services, and insurance. This includes general human resources costs and procurement costs for the UAS fund.There is often no legislated maximum, however NGOs, philanthropic and charitable organisations tend to cap these costs at between 25 to 35 per cent of total costs.

Programme/ project expenses

Programme expenses or “disbursements” are directly related to carrying out the project or programme. Project/ programme specific goods and services that are procured are included. For example payments of subsidies and grants would be part of programme expenses. In addition payments for procuring assets such as equipment for a project such as a school or hospital connectivity project would be considered project costs. Project specific human resources costs and procurement costs are included in programme/project expenses (e.g. a project manager hired only for the duration of the project, not generally employed by the UAS fund).

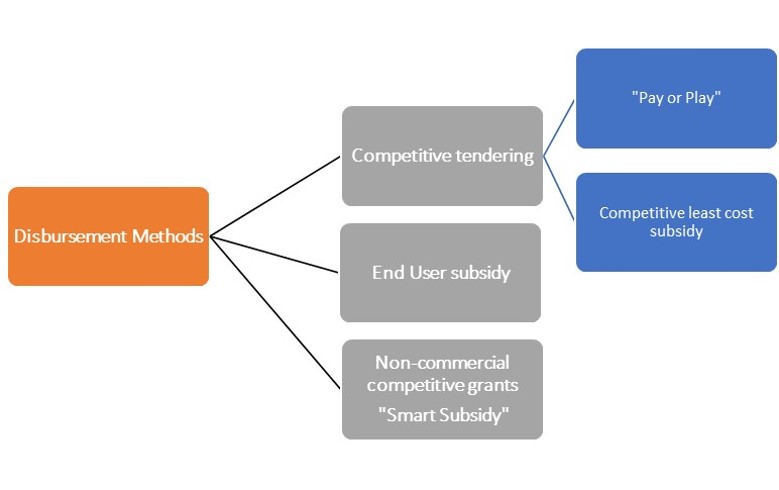

Disbursement options

In general, most of the funding for Funds comes from mandatory contributions made by local telecommunications operators. The amount is usually determined by a percentage of their annual earnings – usually between 0,5% to 2%. In Fund 2.0, the toolkit guides fund managers into diversifying the sources of income, which would lead to more Funding requiring a range of disbursements suitable to the scale of the projects. The illustration below shows the various methods of disbursement that are available to Funds; each method is used for a specific type of disbursement with certain conditions, these conditions are elaborated upon below.

Disbursement methods are often informed by policy and regulatory frameworks that the Fund operates; these often dictate the options of disbursement that the Fund has but also the urgency of the disbursement in each financial year.

1️⃣ Competitive Tendering: Many Funds on the African continent make use of competitive tendering/bidding, due to the common use of the process for public funds; and not because there is a legislative or regulatory mandate to do so. However, this process aligns broadly with many public procurement processes. It should therefore consider the OECD principles set out in the box below. In a competitive tendering process, projects are scoped and advertised through a request for proposal; to which eligible bidders respond. The selection is done based a combination of quality of the offering and cost proposed. It does not always assume that the cheapest bid will win, but rather that the winning bid is ‘all round’ the best suited to execute the project (from a financial, technical and ESG perspective, for example).

- “Pay or Play” – A variation of the competitive bidding model is the “pay or play” approach. Operators can either pay their financial contribution or they can “play” and therefore make an in-kind contribution or enter a competitive bidding process to implement projects approved by the Fund management. Often this method is used for big infrastructure projects, rolling out in underserved areas.

- Competitive least cost subsidy – Another popular method of disbursement is the hybrid of competitive bidding and least cost subsidy. The Fund will request that Operators bid competitively for the project implementation, however unlike competitive bidding the consideration is made on the quality of the proposal and the lowest cost that would need to be subsidized by the Fund. The bidders would present the portion that would need to be subsidized by the Fund, and the lowest subsidy that meets the technical quality required would then be awarded the bid. This works best with infrastructure operators and tower companies. While this may work, it is not universally applicable to all projects and all programmes; this approach to disbursement works best with projects such as the following:

- Large capital projects in network infrastructure

- Large sums of subsidies to be disbursed

- Tower Companies as subsidy recipients.

2️⃣ Non-commercial but competitive grants: This form of disbursement is also known as a Smart Subsidy. The Fund will stipulate specific guidelines which are aligned to specific targets in the project. This subsidy has very specific characteristics such as:

- It should be a once off subsidy;

- It should kick start a project or service with the objective of ultimately seeing the programme become self-sufficient or commercially viable;

- It is designed to encourage cost saving and market growth;

- In addition, like all subsidies, it should:

- Encourage service provision in areas where, without the subsidy, investors might otherwise have been reluctant to invest;

- Link the subsidy to optimal results;

- Be designed to support cost-minimization incentives; and

- Embody and facilitate good governance[1].

Grants vs Subsidies

Difference between a grant and a subsidy?

Although the terms are often used interchangeably. Grants and subsidies are two different types of funding.

- Grants are sums that usually do not have to be repaid but are to be used for a defined purpose. Unlike loans, grant funding does not have to be paid back.

- Subsidies are direct contributions, tax breaks and other special assistance that governments provide businesses to offset operating costs over a lengthy period. The main rationale for granting subsidies is to stimulate investment that would otherwise prove too costly for operators to pursue, such as closing the access gap.

3️⃣ End user subsidy: this type of subsidy is predominantly used in demand side projects that are designed to subsidies end user products to a specific group of the population such as the elderly, people with disabilities, or schools. These subsidies are usually channeled through contributing operators, where end users can easily register, go through a vetting process and be given end user devices. In many countries End user subsidies are complex to implement, especially where there is no central data based that can verify the person and the category in which they qualify; such as social grant or biometric ID.

USAF 2.0

On one hand, in some countries, the reformed UAS fund needs to balance concerns that the levy is a ‘tax’ and that the funds are not ring-fenced. These two concerns can be resolved through using sector-generated monies for contributions, i.e., through fees and taxes for UAS.

On the other hand, USAF 2.0 needs to expand its sources of funding. With digitalization it has been argued that the ICT sector finds itself in need of expanding its contribution base beyond those who have traditionally participated (predominantly network operators contributing through investments along with telecommunication- specific levies, licence and spectrum fees). As the benefits of the digital economy expand to all sectors, including notably areas not traditionally seen as involving ICT, other companies in those sectors can be encouraged and incentivized to contribute in order to increase their benefits.” (UN Broadband Commission)

If funds continue to be limited to mandatory contributions by a select group of operators, it is difficult to argue for the broadening of the scope of beneficiaries. It might then make sense to prioritise the financing of parties that have contributed to the extent that they obtain the funding on a competitively neutral basis. In this case, pooling resources and extending the sources of funds may reach more beneficiaries. An innovative means of sourcing alternative funding is through the fund of funds model. This, however, requires that the fund has sufficient governance mechanisms and credibility. This credibility would be demonstrated through the trust and reliability of the fund as demonstrated over a sustained period. The fund of funds model could be implemented in two ways:

- The UAS fund as an investor in a fund of funds (New Zealand Seed Co-Investment Fund), European Investment Fund) adds an intermediary layer of skilled and experienced fund managers and in so doing assist funds that do not have the skills and capacity to make project- and investment-decisions. However, this would also take the fund one step away from the projects and could compromise the impact and ability to be outcome-based. The ‘intermediary layer’ could, for example, influence project implementation in a way that deviates from the scope of UAS.

- The UAS fund as the fund of funds (Republic of Korea). This ‘investor’ in projects model requires the fund to be highly credible, have a good track record of disbursements, high accountability and high transparency. In the absence of these traits, it will not be able to find investors to put money into its fund of funds. If, as is the case in the Republic of Korea, investment from other public funds is pooled, while efficiencies are achieved using this model, the stakes increase if the fund is misused or not disbursed.

Sector-generated tax-retention mechanisms

Fees and taxes that are specific to parties operating in the digital or ICT space include:

- operating license fees;

- spectrum license fees;

- UAS contributions;

- digital or content tax;

- rights of way and recurring fees linked to telecommunication infrastructure;

- equipment import fees (both for network and user equipment).

The Broadband Commission Working Group on 21st Century Financing Models for Sustainable Broadband Development recommends that a portion of any such tax revenue is earmarked to finance digital infrastructure development and broadband adoption. This revenue could be disbursed through a dedicated digital fund or a reformed version of the UAS fund.

Source: 21st Century Financing Models for Bridging Broadband Connectivity Gaps

Beneficiaries

The beneficiaries of UAS funds have primarily been operators and equipment vendors through least-cost subsidies and competitive bidding processes, low-income users through end-user subsidies, and projects that support funds’ mandates, such as schools (e-rate and school connectivity projects) and communities through telecentre projects. With a broader scope, the pool of eligible beneficiaries may need to be widened. The term “beneficiaries” in this context refers to direct beneficiaries, i.e. recipients of money from the fund, as opposed to the people who broadly benefit from a project. The following questions are instructive for assisting policy-makers and Fund Administrators to identify the options and barriers to extending the types of beneficiaries:

- Who are the contributors to the UAS fund (list)?

- Who are the beneficiaries (list)?

- Is there a problem in principle with parties who did not contribute to the UAS fund, receiving subsidies and grants from the fund (i.e. being beneficiaries)? Is there a legislative limitation in this regard?

- Is there a problem in principle with private parties who are not licensed (whether or not they contributed to the fund) receiving subsidies and grants from the fund (i.e., being beneficiaries)? Is there a legislative limitation in this regard?

- How would the fund treat applications for funding from parties that are not licensed and not contributors, such as platforms, OTT service, applications providers, communities using unlicensed spectrum? Is there a legislative limitation in this regard?

- Who are the public sector beneficiaries from the fund (e.g. schools, hospitals, clinics)? On what basis are they selected? Are there any limitations on public sector beneficiaries from the fund?

Fund Administration

Principle: Efficient and effective fund administration is imperative

Fund management and administration has been approached either through a ministry (e.g. Colombia, Republic of Korea), a division of the regulator (e.g. Eswatini, Malaysia, Uganda,) or a separate agency (e.g. France, Nigeria, Peru, South Africa,). The principles of good governance ensure that funds are transparent and accountable and operate with integrity.

The box below sets out the key administrative and governance criteria for an established fund. These requirements remain key even in the digital era. They are basic requirements for USAF 2.0 to be able to function optimally and sustainably and deliver on the mandate . There is a need not only in terms of resources, but also to ensure an objective, strategically positioned board.

Ringfencing ensures that funds are not reallocated to the general national budget or spent on other national development priorities. Where there is no ringfencing there is a risk that the ICT sector contributions are used to fund other sector priorities. Ringfencing also stimulates confidence amongst investors on the sound financial governance of the projects.

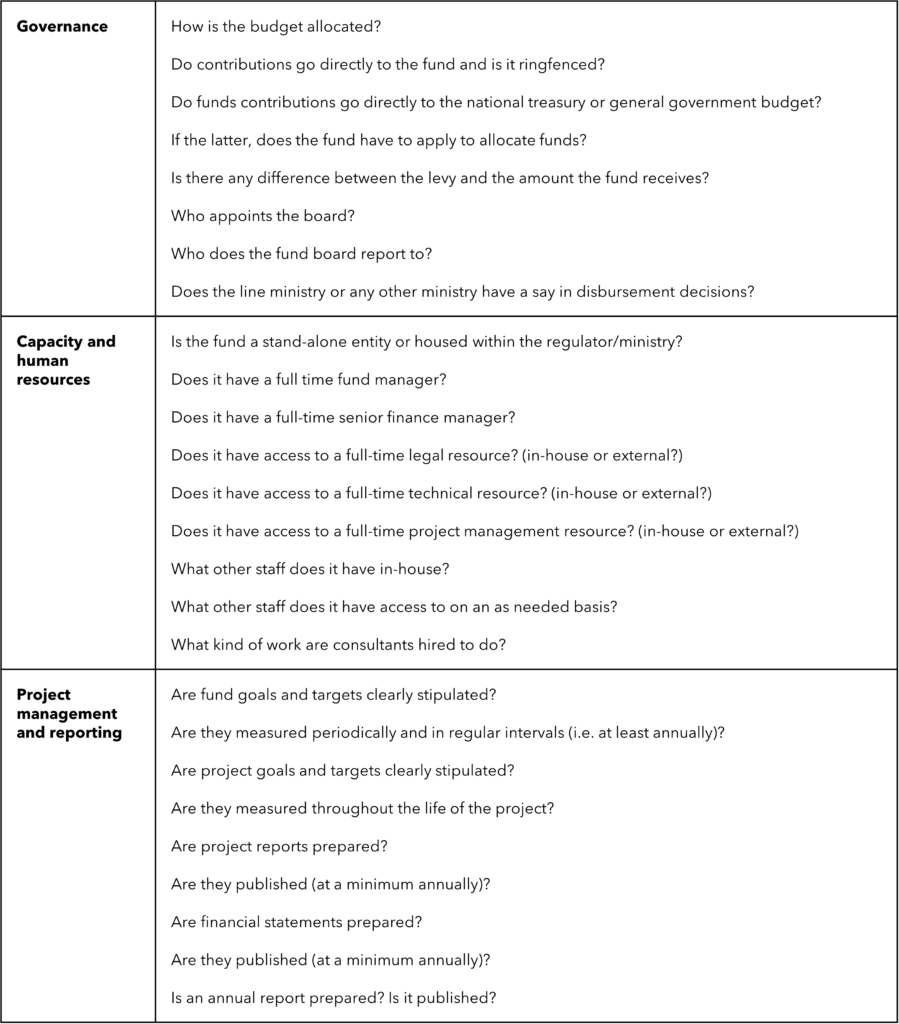

Fund administration checklist (all mandatory)

Without the following, a fund cannot effectively proceed to a USAF 2.0:

✅ A qualified fund manager/CEO and management team that includes technical, project management, legal and financial expertise.

✅ An objective board.

✅ Funds are ringfenced and in a separate bank account managed by the fund.

✅ Audited annual financial statements are required.

✅ Published application procedures, often captured in a fund manual.

✅ Requirements for periodic reporting, and annual audited accounts.

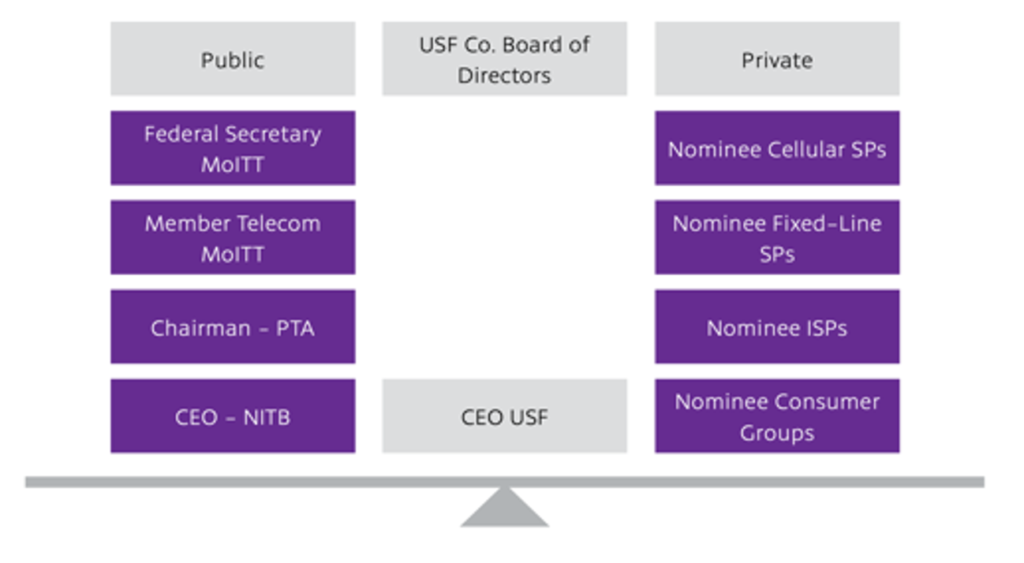

Download checklistCase study: Pakistan USF Board (balanced external, stakeholder representative)

The Universal Service Fund was established by the Government of Pakistan (Ministry of Information Technology). The Universal Service Fund promotes the development of telecommunication services in un-served and under-served areas throughout the length and breadth of the country.

The current board is broadly representative of industry and includes senior (executive and chairman level) representatives of:

- Consumer protection body

- Ministry of Information

- Operators (Telenor, Supernet and Pakistan Telecom)

- CEO of the USF

Boards should also be inclusive in terms of gender, disability and age to lead by example and ensure adequate representation.

Source: Pakistan USF Company

Case Study: Mozambique and Eswatini (internal unit, same board as regulator)

The Universal Access Service Fund, Fundo do Serviço de Acesso Universal (FSAU, UASF) in Mozambique is a separate internal unit and account under the national regulator, Instituto Nacional das Comunicações de Moçambique (INCM) and is managed by the Executive Secretary of the UASF Internal Unit. The Executive Secretary of the UASF reports directly to the Board of Directors of INCM and works in coordination with other departments within the regulator. The Board of INCM oversees the activities and decisions of the UASF. [1] The Universal Access Service Fund, in Eswatini is a separate internal unit and account under the national regulator, ESSCOM. It is managed by the manager of the UASF Internal Unit who reports directly to the Board of Directors and CEO. He works in coordination with other departments within the Regulator. The Board of ESSCOM oversees the activities and decisions of the UASF.

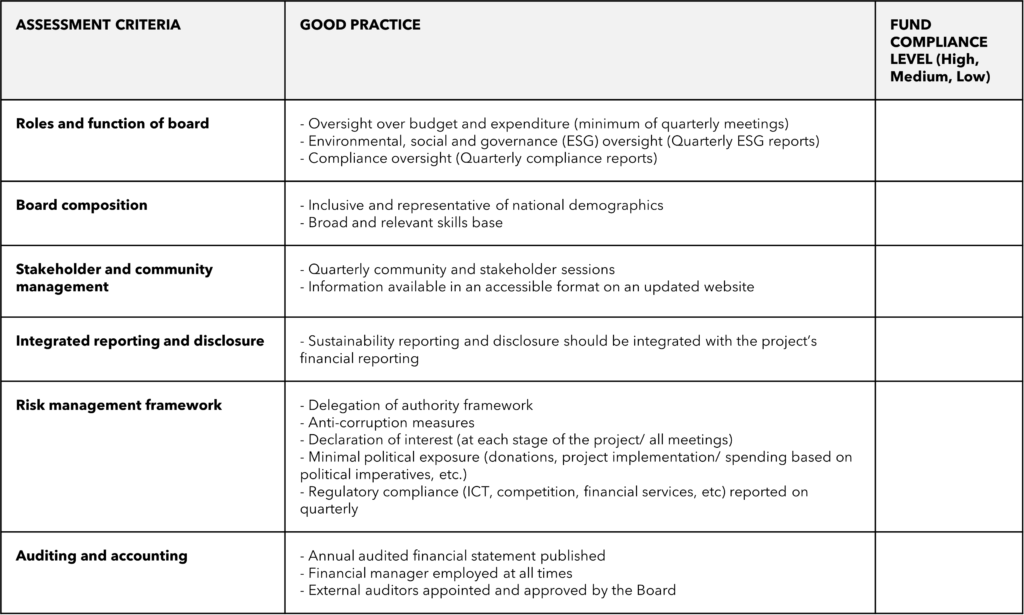

Governance, Transparency and Accountability

Principle: UAS funds must publish accounts, reports and audits

Good governance is an important element of USAF 2.0 model, which has increasingly been included in the assessment and measurement of the effectiveness of the fund, as is done for Development Finance Institutions and corporate boards, given its significance and materiality. Transparency and accountability are cornerstones of good governance.

Furthermore, USAF 2.0 governance principles have to facilitate collaboration and align with global environmental, social and governance (ESG) standards. Therefore the appropriate structures need to be in place.

Template for measuring good governance (to be completed by the fund)

Examples fund manuals

| Botswana | Manual of Operating Procedures https://www.bocra.org.bw/uasf-manual-operating-procedures |

| Eswatini | Universal Service Operating Manual https://www.esccom.org.sz/universalservice/ Universal_Service_Operational_Manual.pdf |

| United States | https://www.usac.org/about/universal-service/ |

Scope and mandate / eligible projects

Principle: The digital ecosystem and the total cost of participation must be taken into account

Traditionally, universal service strategies and funding focussed primarily on closing infrastructure gaps. The entire universal access framework was informed mainly by a gap analysis model which has as its premise that there are various geographical ‘zones’ that need to be covered. The market efficiency, smart-subsidy and true access gaps, which represent areas beyond which commercially motivated roll-out is unlikely, required different strategies and funding models to be addressed. Given that supply side funding for the expansion and extension of networks has been a central part of fund mandates, it is written clearly as such in most founding legislation.

Notwithstanding the main focus of traditional funds on incentivising operators to extend their networks, in exceptional cases – mainly deep rural and remote areas and for certain low income population groups – affordability would be a challenge and end-user subsidies would be required. In some countries such as Eswatini, Ghana, and the United States, subsidies were extended to schools via an e-rate scheme. As such, many funds specifically refer to project types or beneficiaries in their legislation, e.g., school connectivity, e-rate or connection of clinics. In this case, the law makes specific provision for the support of projects that connect schools and health centres, but not other strategic public institutions that are central to a given community, such as police stations or financial centres.

With the evolution of technology and digitalization, it has become clear that current laws fall short in terms of what is required. To assess and identify areas that need to be addressed to evolve to UASF 2.0, the policy-maker and fund administrator should consider the following checklist to review legislation to facilitate the funding of digital technologies and services:

✅ Legislation or regulation limits the scope of intervention to one or two sectors (e.g., education and health)

✅ Legislation or regulation does not cater for the implementation of adoption, access and usage strategies

✅ End users, both individuals and institutions, are not considered as potential beneficiaries (only those that contribute can benefit)

✅ Digital inclusion and access for marginalized and vulnerable communities is not catered for in legislation or regulation

✅ The fund framework does not recognise the multitude of potential funds, investors and financiers and does not support collaboration

USAF 2.0 role

In order to address digitalization, the USAF 2.0 mandate (to which the strategy and associated programmes will be linked) should be defined more broadly than it has been historically.

- At an infrastructure level, the focus should extend beyond last mile connectivity and USAF 2.0 should also focus on high capacity, high speed digital backbones, i.e. fibre-optic cables, such as in India, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Pakistan. It should also consider supporting international connectivity and IXP projects with the aim of providing affordable access to international fibre-optic connectivity.

- Beyond infrastructure, the USAF 2.0 should be allowed to support the whole digital value chain.

In addition, USAF 2.0 policy, legislation and regulations (USAF framework) should be aligned with the following checklist:

✅ Universal service and access should be defined without reference to specific sectors given the cross-cutting nature of ICTs, and without project types prescribed in too much detail in legislation, given the fast pace of change and innovation in the sector.

✅ UAS targets should be aligned with the development agenda and should consider how ICTs can enable meeting these goals as this will be the guiding principle in the definition of projects and beneficiaries.

✅ UAS targets should be aligned with the development agenda and should consider how ICTs can enable meeting these goals as this will be the guiding principle in the definition of projects and beneficiaries.

✅ The USAF framework should enable the fund to disburse funding for supply-side and demand-side projects and should be broadly defined so as not to restrict implementation. As part of a new, holistic digital USAF (USAF 2.0) strategy, this mandate needs to be extended beyond infrastructure deployment (which still remains key) but also to areas such as adoption, skills and capacity development and research and development.

✅ Inclusion must remain core to the mandate of the fund.

✅ The fund should be allowed to collaborate and to use a number of finance mechanisms and funding models that will assist in reducing investment risk and lowering the costs of enabling digital access in and to underserved communities, and in so doing spur private investment.

✅ The fund should be able to spend money on tools that will facilitate investment in underserved areas and to underserved communities and are the fundamental building blocks of any UAS strategy such as baseline data, infrastructure mapping technology, and other forms of research.

From a funding perspective, collaboration is a key aspect of the mandate that needs review for many funds, especially with the increased funding required to meet the broader and cross-sectoral needs. Funds should be able to collaborate with public and private financiers who have complementary objectives. This is central to the new USAF ability to leverage funds.

Autonomy

In some countries, it has been argued that funds are not sufficiently independent to be trusted with large amounts of money, or to be relied upon to stick to the strategy that has been agreed. It is important for fund autonomy that, in the audit process, the USAF assesses its ability to operate without political interference. The governance framework, skills, human capacity and resources and project management and reporting systems are important elements of the institutional framework and are key to building trust.

Questionnaire to assess autonomy

B.3.3 New roles for USAF 2.0 in the context of innovative funding models

Not all funds are ready to evolve to the USAF 2.0 model, especially the pooling of funds and collaboration with others. This evolution is only appropriate for funds with high levels of governance, a history of disbursements, and credibility in the market. Where a fund does evolve and the mandate is reviewed, some new roles may be considered.

B.3.3.1 Collaborative and advisory role

Given its unique position in the ICT sector, USAF 2.0 can differentiate itself by adding an advisory or facilitating role to its funding, which could entail collaboration, insight and advice, and pilots and scale:

Collaboration:

- Convening various funds and financiers interested in digital infrastructure, innovation and adoption, as well as digital inclusion.

- Coordinating the pooling of government resources in line with a whole-of-government approach. The Republic of Korea’s allocation of funds shows that governments can pool money from different departments and agencies dealing with one theme, e.g. SMEs, and use it to increase the size of the fund. If this approach is taken, it can coordinate government-funded initiatives and complement or replace the mandatory levies, depending on the funding gap in a given country.

Insight and advice:

- Filling knowledge gaps between financiers with no specific knowledge or understanding of the ICT and digital sectors and a USAF 2.0, which is able to design and develop concepts and terms of reference for successful broadband and digital transformation projects that consider connectivity, access and use across the economy.

Pilots and scale

- Using USAF projects as a model for national-scale projects so that it can collaborate and align with the regulatory regime (e.g. sandboxes) and private initiatives (e.g. accelerators) to make a meaningful impact. USAF 2.0 should evolve the use of “pilots” and invest in scalable pilots. This can be done alongside the traditional role of funding and piloting projects.

Is the existing fund ready for collaboration?

Values and mindset

✅ The fund embraces collaboration.

✅ The management team has a catalytic mindset.

✅ Sustainability is a core value.

✅ Shift focus from solely implementing projects to leveraging investment in projects.

Mandate

✅ USAF founding legislation allows for private sector investment or finance.

✅ The fund has the authority to use financing instruments other than grants and subsidies, such as concessional loans, equity investments or loan guarantees.

Organisation

✅ The fund has management capacity.

✅ Staff of the organisation is equipped to deal with new types of funding and should have the skills and experience related to structured public-private funds.

✅ The fund can effectively work with private funds and institutional investors.

✅ A coordination mechanism is in place for cross sectoral financial cooperation among government bodies.

Impact

✅ The fund has a formal mechanism in place to track and measure impact.

✅ There is a clear, consistent and documented reporting framework.

✅ There is a clear, effective and documented monitoring and evaluation process in the organisation. Staff has the skills and experience related to the monitoring and evaluation of projects and of structured public-private funds.

Precedent (Yes/No, if Yes then factor the lessons learned into the fund design)

✅ Has the fund ever participated in a project that utilises innovative funding models including blended finance?

✅ Are there any funds in the country that have been established and given mandates to use innovative funding models, including blended finance?

Download checklistB.3.3.2 Application of innovative finance models

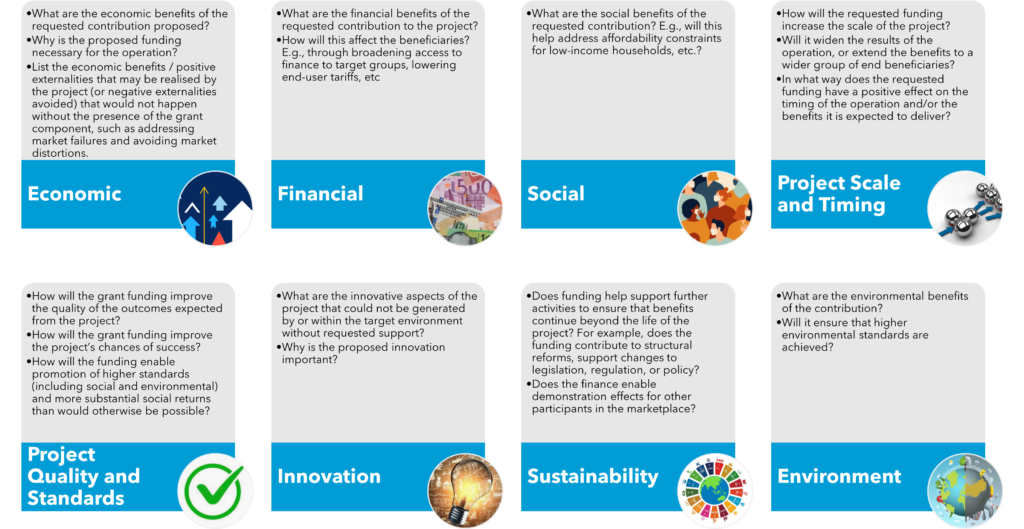

Historically, funds have mainly issued grants and subsidies through least cost subsidies and competitive bidding processes. In addition to issuing grants and subsidies, USAF 2.0 encourages co-investing, leveraging and pooling resources to stretch its funds and impact. In order to assess its readiness to progress to the application of more complex funding models, the fund should consider:

- Legislative mandate: What types of financial support is the fund permitted to provide?

- History: What types of financial support has the fund actually provided? Has the fund co-invested, partnered, and/or pooled resources?

- Governance: How have competing applications for USAF funds been adjudicated? Are there standard terms and conditions that have been attached to previous funding and project partnerships? Has there been any litigation?

- Transparency: Is there a competitive bidding / least cost subsidy framework? Is there a Fund Manual? Has the manual been published? Has the manual been used to support all funding decisions? (see Public procurement process design and principles checklist as a guide)

USAF 2.0 financing toolkit can move beyond grants and subsidies, and complement existing tools with innovative funding models, in particular, it can be positioned to support:

- through, amongst others, providing funding and advisory support for school connectivity projects and the connection of other strategic institutions; and

- through providing funding and advisory support form community network projects, as well as facilitating their collaboration with other parties such as operators and municipalities.

Additionally USAF 2.0 can be designed to support projects that use a blended financing model. As it evolves, USAF 2.0 will require more than just its own sources of revenue, even if they are expanded. The fund will be required to mobilise additional and external sources of finance. This role in blended financing is detailed more in the next section. This will increase the impact of USAF contributions and projects and accelerate progress towards using digital technologies to achieve the SDGs.

Other innovative funding models such as venture capital and crowdfunding , which would be best applied to SME development, innovation and some adoption projects, may be too risky at this stage to be applied by USAFs. The challenge lies in the intrinsically higher risk profile of venture capital projects where an idea is being backed, and in the lack of control of the project and its outcomes in the case of crowdfunding.

B.3.3.3 Blended finance

Blended finance is a tool that can complement the work of USAF 2.0 given that:

- it should only be used when the public benefit of a project exceeds the returns to private investors, usually because there are externalities, market failures, affordability constraints, or information deficiencies in the market that prevent dynamic development of the private sector;

- it should seek to develop and encourage future sustainable commercial markets where it is applied.

USAF 2.0 should note that blended finance approaches are centred on the concept of additionality, which represents a shift from the thinking of traditional funds. Additionality refers to the extent to which development-oriented public money leads to private investment that would not have otherwise been made if not for the public investment. Additionality could be financial, e.g. financing on terms not available from the market, including mobilization; or non-financial, e.g. non-commercial risk mitigation, technical assistance and strengthening regulatory and policy environments.

Applying blended finance principles enhances USAF 2.0 beyond its previous iteration in that it forces the fund to consider the “additionality” of the coordinated intervention being made whether that intervention is being made in the form of grants, subsidies, guarantees, or technical assistance.

The flowchart below sets out the decision-making process for funds seeking to apply blended finance.

Additionality is meant to be measured ex ante (i.e. before the project starts), and set out what will happen if the funding is not received. If there is no additionality, there is no basis for the provision of the finance. The ex post additionality (what happened because the funding was made available?) is then measured against what was expected, usually based on information that was provided by the applicant at the time the request was made for funding. It is often measured in two main parts – both of which are important to USAF 2.0 in fulfilling its mandate:

- Financial additionality – blended finance is necessary to ensure the project gets finance and can be implemented;

- Developmental additionality – blended finance helps the project achieve better development results.

Ensuring additionality in blended finance

- Blended finance transactions need to provide both development and financial additionality beyond what can be achieved through public or private finance.

- In terms of both development and financial additionality, the incremental outcomes catalysed by a blended finance transaction beyond what public and private finance alone would be able to deliver needs to be clearly identified and should be able to be quantified.

- Additionality is transaction-specific and context-specific. It is driven by unique country, sector, market and project characteristics:

- to enable ex post impact assessments for a selected sample of blended finance transactions, donors should request that ex-ante baseline data is collected on key results indicators and monitored during implementation;

- governments and donors should encourage and facilitate a harmonised approach towards assessing additionality in development finance, including for blended finance, and reporting on additionality in a standardised way.

There is no single standard for measurement of additionality, however, the EU provides guidance in that regard (see figure above). Additionality is one of the principles that underpins the approach to funding that is taken by the European Structural and Investment Funds. Accordingly, they seek to ensure that contributions from the funds must not replace public or equivalent structural expenditure by a Member State in the regions concerned by this principle. In a USAF context, the funding should not ‘crowd out’ other available sources of funding, whether these are public (e.g. other funds and subsidisation programmes) or private. The OECD furthermore provides detailed guidance on measuring the impact of blending in its recent publication “Evaluating Blended Finance and Instruments: Approaches and Methods”

Blending risks

The fund must be aware that blended finance is one of many tools and that the risks associated with it include:

- Projects sought by other parties (donors, private sector, etc) may not align closely enough with country or sector plans that the fund is supporting, although at the highest level most funds are now aligning to SDGs targets.

- Different funding actors have different standards for transparency, accountability, and stakeholder participation.

- Ownership and accountability may be difficult to agree upon and/or implement on the ground.

- Preferential treatment may be given to the partners, vendors, operators of the largest funds and technical and other service providers, making local procurement challenging.

- Weaknesses in monitoring and evaluation systems, or inadequate definitions of additionality, may allow projects to proceed in the absence of demonstrable impacts or on the basis of financial performance.