5.2. The Need for International Cooperation

5.3. Current Models of International Cooperation

5.4. Areas for Potential International Coordination in Legal Efforts

5.5. International conventions and recommendations

5.6. Promoting a Global Culture of Cybersecurity

5.7. Strategies for integration and dialogue

5.8. Initiatives by the Private Sector/Industry/Academia/Government

5.9. Strategies for multi-stakeholder partnerships

5.10. International Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs)

5.11. Strategies for information-sharing - Cyber Drill exercises

Today’s global ICT networks connect everyone. Computing capabilities, telecommunications and the Internet now transcend borders, negating frontiers and reducing distance, and creating a global information society. Countries, economies, government and firms have come to depend on ICT systems, but are now interconnected, linking people and objects, and exchanging information in new ways. Global interconnectivity brings with it new possibilities for digital disruption, requiring a sea-change in how we must view, prioritize and deal with information security.

It is vital that countries can respond to cybersecurity threats and other information security and network security issues in a timely manner. They must ensure that there organized structures exist within their own jurisdiction to protect cybersecurity and be able to cooperate in a manner that allows countries to respond to cyber-threats swiftly and quickly.

There are a number of vehicles for international cooperation that have been established to respond to cyber-threats, enhance cybersecurity and stimulate dialogue between stakeholders. Such vehicles can be international inter-governmental; regional inter-governmental or Private and Public Partnerships Countries must take advantage of these vehicles for international cooperation. However, awareness of these vehicles for international dialogue is sometimes lacking.

ITU has played a leading role in this area and provides a platform for countries to agree on common principles that have benefited governments and industries dependent upon ICT infrastructure. ITU also plays a leading role in capacity-building in cybersecurity, with the work currently being undertaken by ITU-D. This chapter discusses efforts to develop and enhance frameworks for international cooperation in cybersecurity. It gives examples of how different organizations are interacting and collaborating on common platforms to promote cybersecurity.

5.2. The Need for International Cooperation

The need for international cooperation in cybersecurity is evident, due to the nature of cyberspace itself. Cyberspace or the Internet is “borderless” in nature. Offenders can be located in one country and commit a crime using a computer or network in another country, without ever leaving country of origin. The borderless nature of the Internet enables malicious individuals and groups to exploit “loopholes of jurisdiction”, making investigation and law enforcement difficult. Perpetrators can act from any location in the world and mask their identity.

The case for international cooperation is even stronger, when criminals take advantage of countries’ inability to coordinate, due to legal reasons or because authorities do not have the necessary technical expertise or resources to address the issue. Cybercrimes are not always clearly illegal in some jurisdictions. Further, it is easy to learn how to commit a cybercrime, which often needs few resources relative to its impact (Figure 2.3 in Chapter 2).

Cyber-attacks are independent of time and place. Cyber-defense is hard - criminals are now in possession of rapidly renewable arsenals of attack weapons, that can potentially cause global harm. Authorities must observe jurisdictional boundaries and due legal procedure – niceties that criminals need not consider. Further, cyber-criminals need find only one vulnerability to exploit, while ICT security professionals and software must guard against many different types of vulnerabilities. As vulnerabilities increase, threats in cyberspace are growing rapidly. The rate at which new viruses emerge – often up to 20 a day – the overwhelming presence of spam, the sophistication of phishing sites and the spread of implanted botnets all give cause for concern.

Cyber-criminals are no longer playful hackers, but are now well-organized in profitable conglomerates with substantial economic and technological resources. Cyber-criminals are increasingly developing new attack software, which soon find its way onto the black market. Beyond profits, these groups may also be driven by more sinister motives for political gain. It is easy to imagine how cyber-terrorists or states or other groups intent on cyberwar can take advantage of the potential of these tools and software for causing damage.

5.3. Current Models of International Cooperation

This section gives examples of models of international cooperation at work.

5.3.1. Regional cooperation

Due to the global nature of information networks, no policy on cybersecurity can be effective, if efforts are confined to national borders. Sovereign states should participate in international discussions. Regional operational cooperation remains a major challenge in the area of cybersecurity. When confronted with cyber-attacks, mutual assistance has often proven ineffective and new cooperation structures are not yet sufficiently developed.

A coordinated approach includes the exchange of information and best practices. Countries from specific regions should work with neighbours, with regional initiatives open to others. Each country should establish a central point-of-contact to act as a liaison. Developed societies are well-positioned to contribute to the establishment of internationally secure and the development of a safe environment. They can share best practice as inspiration to other counties.

As cyber-threats and other information security and network security issues have become borderless, international cooperation should be based on partnership with organizations from other countries in areas such as information-sharing, early warning, monitoring and alert networks. Countries need to establish national strategies incorporating international cooperation.

At the regional level, important initiatives have been undertaken, for example, by the European Union, the Council of Europe, the G8 Group of States, Asian Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), Organization of American States (OAS), the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN), the Arab League, the African Union and Network Operations Groups (NOG).

5.3.2. International cooperation

While online criminal activities are constantly evolving, criminal structures are better organized and more efficient. International cooperation is lagging behind and has difficulty keeping pace. The cross-border nature of cyber-attacks and the organization of criminals necessitate international cooperation actions through justice and police systems. Cybercrime is a phenomenon with effects far beyond the borders of the nation-state. Countries should take a proactive role in international initiatives, especially in the exchange of information and best practices, training and research. Capacity-building in organizational structures (including policies, roadmaps and strategies) is vital.

Frameworks for international cooperation have been put in place by a number of organizations. ITU has launched the ITU Global Cybersecurity Agenda. The Council of Europe’s Convention on Cybercrime is one of a number of regional initiatives (Chapter 1). International cooperation can also work well, where countries develop watch and warning networks, with real-time sharing of the threat information. There is currently no global governance system to control spam., where international cooperative action is based on bilateral and multilateral platforms.

The global nature of the legal, technical and organizational challenges related to cybersecurity can only be properly addressed through a strategy that takes into account the role played by all relevant stakeholders and existing initiatives in a framework of international cooperation. At international level, important initiatives have been undertaken by:

• United Nations General Assembly;

• International Telecommunication Union (ITU);

• Interpol / Europol;

• The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD);

• UN Organizations on Drug and Crime Problems (UNODC)

• UN Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute (UNICRI);

• Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN);

• International Organization for Standardization (ISO);

• The International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC);

• Internet Engineering Task Force;

• FIRST (Forum of Incident Response and Security Teams).

5.3.3. Legal Measures

5.3.3.1.Convention on Cybercrime

The Council of Europe (CoE) has been working to address growing concerns over the threats posed by hacking and other computer-related crimes since 1989, when it published a study and recommendations addressing the need for new substantive laws criminalizing certain conduct committed through computer networks. The Convention on Cybercrime is a regional initiative seeking to address cybercrime by harmonizing national laws, improving investigative techniques and improving cooperation among nations, that entered into force on 1 July 2004. It deals in particular with infringements of copyright, computer-related fraud, child pornography and violations of network security. It also contains a series of powers and procedures such as the search of computer networks and interception (see Chapter 1).

Its main objective is “to pursue, as a matter of priority, a common criminal policy aimed at the protection of society against cybercrime, inter alia, by adopting appropriate legislation and fostering international cooperation”. The Convention seeks to harmonize the criminal substantive law elements of offences and cybercrime, providing for the domestic criminal procedural law powers necessary for the investigation and prosecution of such offences. It seeks to set up a fast and effective regime of international cooperation.

The Convention has been supplemented by an Additional Protocol making publication of racist and xenophobic propaganda via computer networks a criminal offence. In 2007-2008, the CoE reviewed whether a separate instrument was needed for cyber-terrorism and concluded that countries should fully implement existing instruments, in particular the Convention on Cybercrime, rather than developing a new treaty.

5.3.3.2.Existing UN International Provisions

The UN Convention against Transnational Organized Crime was adopted by General Assembly resolution 55/25, of 15 November 2000. It is the main international instrument in the fight against transnational organized crime, and seeks to promote international cooperation to prevent and combat transnational organized crime more effectively.

Although the Convention does not provide a single, agreed definition of organized crime, its provisions do provide elements of a clear concept of organized crime. For instance:

• Organized criminal group: Three or more persons working together to commit one or more serious crimes in order to obtain financial or other material benefit.

• Transnational crime:

• An offence committed in more than one State;

• An offence committed in one State, but substantial part of preparation, planning, direction or control takes place in another;

• An offence committed in one State, but it involves an organized criminal group that engages in criminal activities in more than one State;

• An offence committed in one State, but with substantial effects in another State.

• Serious crime: conduct constituting an offence punishable with a maximum deprivation of liberty of at least four years or a stricter sanction.

The Convention applies to the prevention, investigation and prosecution of offences in: Articles 5 (criminalization of participation in an organized crime group); Article 6 (criminalization of the laundering of the proceeds of crime); Article 8 (criminalization of corruption); Article 23 (criminalization of obstruction of justice); and other serious crimes, as defined in Article 2 (as defined above). It also states:

“States Parties shall be able to rely on one another in investigating, prosecuting and punishing crimes committed by organized criminal groups where either the crimes or the groups who commit them have some element of transnational involvement”.

5.3.3.3.United Nations system decisions, resolutions and recommendations

There are many decisions, resolutions and recommendations emanating from the United Nations system on a range of areas related to cybersecurity and cybercrime:

• CCPCJ 2007 Resolution 16/2 of April 2007 “Effective crime prevention and criminal justice responses to combat sexual exploitation of children” (especially paras 7, 16).

• ECOSOC Resolution E/2007/20 of 26 July 2007 on “International cooperation in the prevention, investigation, prosecution and punishment of economic fraud and identity-related crime” (E/2007/30 and E/2007/SR.45).

• ECOSOC Resolution 2004/26 of 21 July 2004 on “International cooperation in the prevention, investigation, prosecution and punishment of fraud, the criminal misuse and falsification of identity and related crimes”.

• Para. 18 of the “Vienna Declaration on Crime and Justice: Meeting the Challenges of the Twenty-first century”, endorsed by General Assembly Resolution 55/59 of 4 December 2000 and Para. 36 of “Plans of action for the implementation of the Vienna Declaration on Crime and Justice: Meeting the Challenges of the Twenty-first century” annexed to General Assembly Resolution 56/261 of 31 January 2002.

• Paras. 15 and 16 of Bangkok Declaration on “Synergies and Responses: Strategic Alliances in Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice”, endorsed by GA Resolution 60/177 of 16 December 2005.

• Recommendations by an Ad-hoc Congress Workshop on “Measures to Combat Computer-Related Crime”, held in Bangkok on 22 April 2005 as part of the Eleventh UN Congress on Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice. Para. 2 of General Assembly Resolution 60/177 invites Governments to implement all recommendations adopted by the Eleventh Congress.

• General Assembly Resolutions 55/63 of 4 December 2000 and 56/121 of 19 December 2001 on “Combating the criminal misuse of information technologies”. The latter resolution invites Member States, when developing national law, policy and practice to combat the criminal misuse of information technologies, to take into account, inter alia, the work and achievements of the Commission on Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice.

• Commission on Narcotic Drugs Resolution 48/5 on “Strengthening international cooperation in order to prevent the use of the Internet to commit drug-related crime”.

• Para. 17 of General Assembly resolution 60/178 of 16 December 2005 on “International cooperation against the world drug problem”.

• Commission on Narcotic Drugs Resolution 43/8 of 15 March 2000 on Internet.

• ECOSOC Resolution 2004/42 on “Sale of internationally controlled licit drugs to individuals via the Internet”.

• Various conclusions and recommendations of subsidiary bodies of the Commission on Narcotic Drugs (e.g., the Sub-Commission on Illicit Drug Traffic and Related Matters in the Near and Middle East and regional HONLEA meetings).

• The International Narcotics Control Board (INCB) published recommendations in 2005 to curb the spread of illicit sales of controlled substances, particularly pharmaceutical preparations, over the Internet. INCB is also finalizing a set of guidelines on this.

• General Assembly Resolutions 57/239 of 31 January 2003 and 58/199 of 30 January 2004 on “Creation of a global culture of cybersecurity”, which invite Member States to take note of ongoing cybersecurity collaboration and to promote a culture of cybersecurity.

5.3.3.4.United Nations Crime Congresses

UN Crime Congresses have also considered the technical issues and criminal enforcement associated with computer misuse. In 1990, the UN adopted a resolution on computer crime legislation at the 8th U.N. Congress on the Prevention of Crime and the Treatment of Offenders in Havana, Cuba. The most recent Congress in Bangkok, Thailand, in April 2005 focused on issues of computer-related crime in a special workshop. The Congress report and background paper of the workshop are both available from UNODC. The outcome of the eleventh UN Congress, the Bangkok Declaration on “Synergies and responses: Strategic Alliances in Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice”, called on Member States to further develop national measures and international cooperation against cybercrime and welcomed efforts to enhance cooperation to prevent, investigate and prosecute high-technology and computer-related crime.

5.3.3.5. Other UNODC efforts to combat cybercrime

UNODC published its Manual on the Prevention and Control of Computer-related Crime in 1994. While this publication is now in need of revision, it does serve as a reference. Organized conglomerates of cybercriminals are engaged in the online trafficking of licit drugs and people (human trafficking) and UNODC encourages Member States to take measures to prevent the misuse of the Internet for the illegal offer, sale and distribution of internationally controlled licit drugs.3 Member States can develop policies to terminate such sales through greater coordination between the judicial, police, postal, customs and other agencies.

The International Narcotics Control Board (INCB) has been working actively with experts from governments and concerned industries. During recent meetings of Heads of National Drug Law Enforcement, UNODC has also reviewed measures to counteract new trends in the use of technology by groups engaged in drug trafficking and organized crime. It concluded that most front-line law enforcement agencies are not well-prepared to meet these emerging challenges, either through lack of understanding or lack of technical resources.

UNODC has developed a Virtual Forum against Cybercrime with the Korean Institute of Criminology as a digital platform for law enforcement, judicial officials and academics from developing countries. It will provide training courses and technical advice on the prevention and investigation of cybercrime, with a focus on effective law enforcement and judicial cooperation. Although a regional initiative, experts include representatives from G8 countries, law enforcement and training experts and academics.

In 2007, UNODC launched a Global Initiative to Fight Human Trafficking to raise awareness and build partnerships with governments, NGOs, industry, media etc. Traffickers can now recruit their victims online using online dating, employment and recruitment agencies (e.g. model or artist agencies and marriage bureaux) can be used as ploys to target potential victims. Internet chat websites are often used to befriend potential victims. The risks of young people falling into traffickers’ nets have risen substantially. More information about the methods used by traffickers to recruit their victims online will help formulate appropriate legal, administrative and technical responses.

General Assembly Resolution 56/121 of 19 December 2001 on “Combating the criminal misuse of information technologies” invites Member States, when developing national law, policy and practice to combat the criminal misuse of information technologies, to take into account, inter alia, the work of the Commission on Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice. Among other areas, the Commission is working on the criminal misuse and falsification of identity (identity-related crime), which is relevant when crimes are committed using the Internet and computer-related technology. At the recommendation of the Commission, ECOSOC adopted Resolution 2004/26. Furthermore, and in line with ECOSOC Resolution 2007/20, UNODC continues its efforts to promote further dialogue among experts on best strategies to curb identity-related crime, with two Expert Group Meetings. These initiatives are in line with the Bangkok Declaration, which called on Member States to tackle document and identity fraud and encourage the adoption of appropriate legislation.

5.4. Areas for Potential International Coordination in Legal Efforts

5.4.1. Substantive Criminal Law

To combat global cybercrime, countries must establish some degree of consistency in the definition of substantive offences. On the basis of key regional and international harmonization efforts, countries could criminalize Illegal access, illegal interception, data interference, system interference, misuse of devices, computer-related forgery; and computer-related fraud.

5.4.2. Procedural Law

5.4.2.1.General principles

Adopting appropriate procedural laws, powers and procedures for the prosecution of criminal offences against IT infrastructure is essential for the investigation and prosecution of cybercrime across borders. However, these powers and procedures are also vital for the prosecution of other criminal offences committed over computer systems, and should apply to the collection of electronic evidence of all criminal offences. Such procedures include:

• Powers of expedited preservation of stored data and expedited preservation and partial disclosure of traffic data;

• Production order;

• Search and seizure of stored computer data;

• Real time collection of traffic data and interception of content data; and

• Jurisdiction.

5.4.2.2.Mutual Legal Assistance Agreements

Mutual Legal Assistance is vital for international cybercrime investigations or civil investigations. The rapid growth of networks and the increase in connection speeds allow criminals to transfer their operations between States more rapidly than investigators can follow using traditional investigative techniques. Early on, investigators realized the need to establish contacts and procedures in other countries. The Convention on Cybercrime provides a scheme for mutual legal assistance in electronic cases of investigation of electronic crimes.

5.4.2.3.Identity Management (IdM)

IdM offers the possibility of reducing the need for multiple user names and passwords for each service used, while maintaining privacy of personal information. A global IdM solution could help diminish identity theft and fraud. Further, IdM is one of the key enablers of simplified and secure interactions between customers and services, vital in e-commerce and other online services. Interoperability between existing IdM solutions offers benefits, such as increased trust by users of online services, reduction of spam and seamless nomadic roaming between services.

ITU’s Focus Group on Identity Management was established by Study Group 17 at its 6-15 December 2006 meeting, to facilitate the development of a generic Identity Management framework with the participation of experts on Identity Management. The Focus Group may analyze other aspects related to such a framework. The term ‘IdM’ is understood as “management by providers of trusted attributes of an entity, such as a subscriber, a device, or a provider”, which is not, however, intended to indicate positive validation of a person. The Focus Group on Identity Management aims to:

• Perform requirements analysis based on user case scenarios;

• Identify generic IdM framework components;

• Complete a standards gap analysis; and

• Identify new standards work that ITU-T Study Groups and other Standards Development Organizations (SDOs) should undertake.

For ITU-T purposes, the identity asserted by an entity represents the uniqueness of that entity in a specific context and does not indicate positive validation of a person. Identity management (IdM) is the process of secure management of identity information (e.g., credentials, identifiers, attributes, and reputations). IdM is a complex technology that includes: establishing, modifying, suspending, archiving or terminating identity information; recognizing partial identities representing entities in a specific context; establishing trust between entities; and the discovery of an entity’s identity information (e.g., authoritative identity provider or IdP) that is legally responsible for maintaining identifiers, credentials and some or all of the entity’s attributes.

The establishment of the Joint Coordination Activity for Identity Management (JCA-IdM) was approved by TSAG in December 2007. JCA-IdM Members include representatives from ITU Study Groups and invited representatives from recognized IdM external SDOs and forums. JCA-IdM will report progress to Telecommunication Standardization Advisory Group (TSAG).

5.5. International conventions and recommendations

The UN has long been engaged in work on global issues and is involved in many efforts building confidence and trust in the use of ICTs. Various UN bodies are engaged in significant research and negotiation efforts to build consensus on a number of topics, including setting standards on providing security for networks, establishing a dialogue on a number of problematic issues, including spam and information security, and sponsoring the WSIS.

5.5.1. General Assembly Resolutions

The First, Second and Third Committees of the General Assembly have examined cybersecurity issues and passed a number of resolutions. Relevant UNGA Resolutions include:

• Resolutions 53/70 of 4 December 1998, 54/49 of 1 December 1999, 55/28 of 20 November 2000, 56/19 of 29 November 2001, 57/53 of 22 November 2002 and 58/32 of 18 December 2003 on “Developments in the Field of Information and Telecommunications in the Context of International Security”.

• Resolutions 55/63 of 4 December 2000 and 56/121 of 19 December 2001 on “Combating the Criminal Misuse of Information Technology”.

• Resolution 57/239 of 20 December 2002 on “Creation of a Global Culture of Cybersecurity”.

• Resolution 58/199 of 23 December 2003 on “Creation of a Global Culture of Cybersecurity and the Protection of Critical Information Infrastructures”.

5.5.2. ITU Standards and Working Groups

Standards help guarantee established levels of performance and security in technologies, systems and products and help provide businesses with a systematic approach to information security. ITU is one of the most active bodies in standards development and harmonization. ITU has developed overview security requirements, security guidelines for protocol authors, guidance on how to identify cyberthreats and countermeasures to mitigate risks. ITU’s work on security covers a broad range of activities in security from network attacks, theft or denial of service, identity theft, eavesdropping, tele-biometrics for authentication, security for emergency telecommunications and telecommunication network security requirements.

One of the most important security standards in use today is X.509, an ITU-developed Recommendation for electronic authentication over public networks. X.509 is the definitive reference for public-key certificates and designing applications related to Public Key Infrastructure (PKI). The elements defined within X.509 are widely used in securing connections between web-browsers and servers and agreeing encryption keys for digital signatures, email and e-commerce transactions. ITU’s X.805 Recommendation defines the security architecture for systems providing end-to-end communications that can provide end-to-end network security, enabling operators to pinpoint and address network vulnerabilities. ITU’s Security Framework extends this with guidelines on protection against cyberattacks.

Study Group 17 is the Lead Study Group on Communications System Security and handles security guidance and the coordination of security-related work across all ITU-T Study Groups. It is responsible for studies on security, the application of open system communications (including networking and directory), technical languages and other issues related to the software aspects of telecommunication systems. It has approved over one hundred Recommendations on security.

5.5.3. Educational and Research Bodies

Academic conferences have also provided ideas that have later appeared in national legislation. Examples include the University of Wurzburg Conference in 1992, which introduced 29 national reports and recommendations for the development of computer crime legislation. Another example is the December 1999 Conference on International Cooperation to Combat Cybercrime and Terrorism, organized by Stanford University in California, which resulted in a Proposal for an International Convention on Cybercrime and Terrorism.

5.6. Promoting a Global Culture of Cybersecurity

5.6.1. Different Perspectives

A global approach to promoting cybersecurity must take into account all the different actors in the information society. An appropriate culture of cybersecurity should be developed through a global framework for end-users (including children); technologies, service or content professionals and providers; policy-makers; professionals and law enforcement officials.

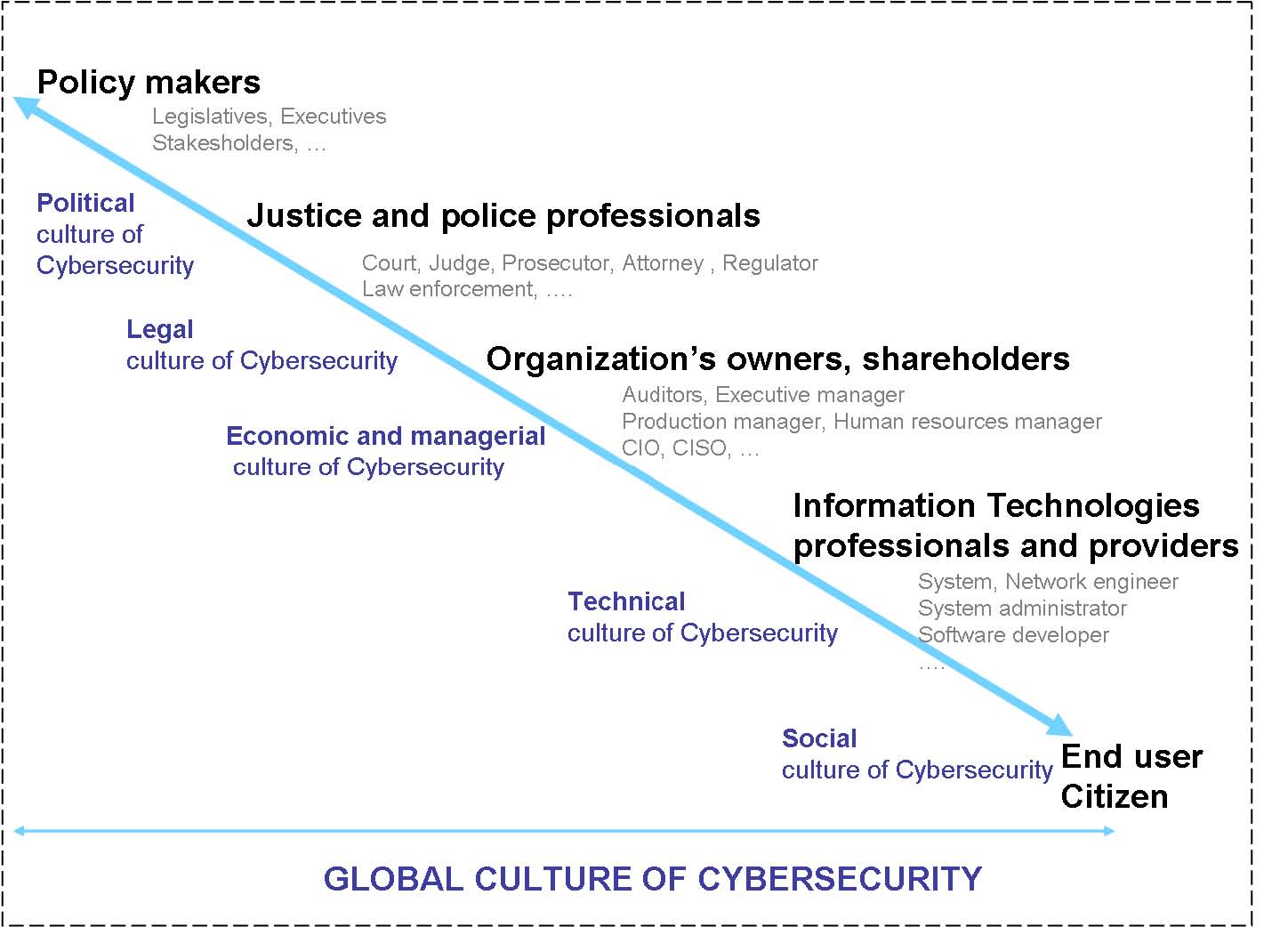

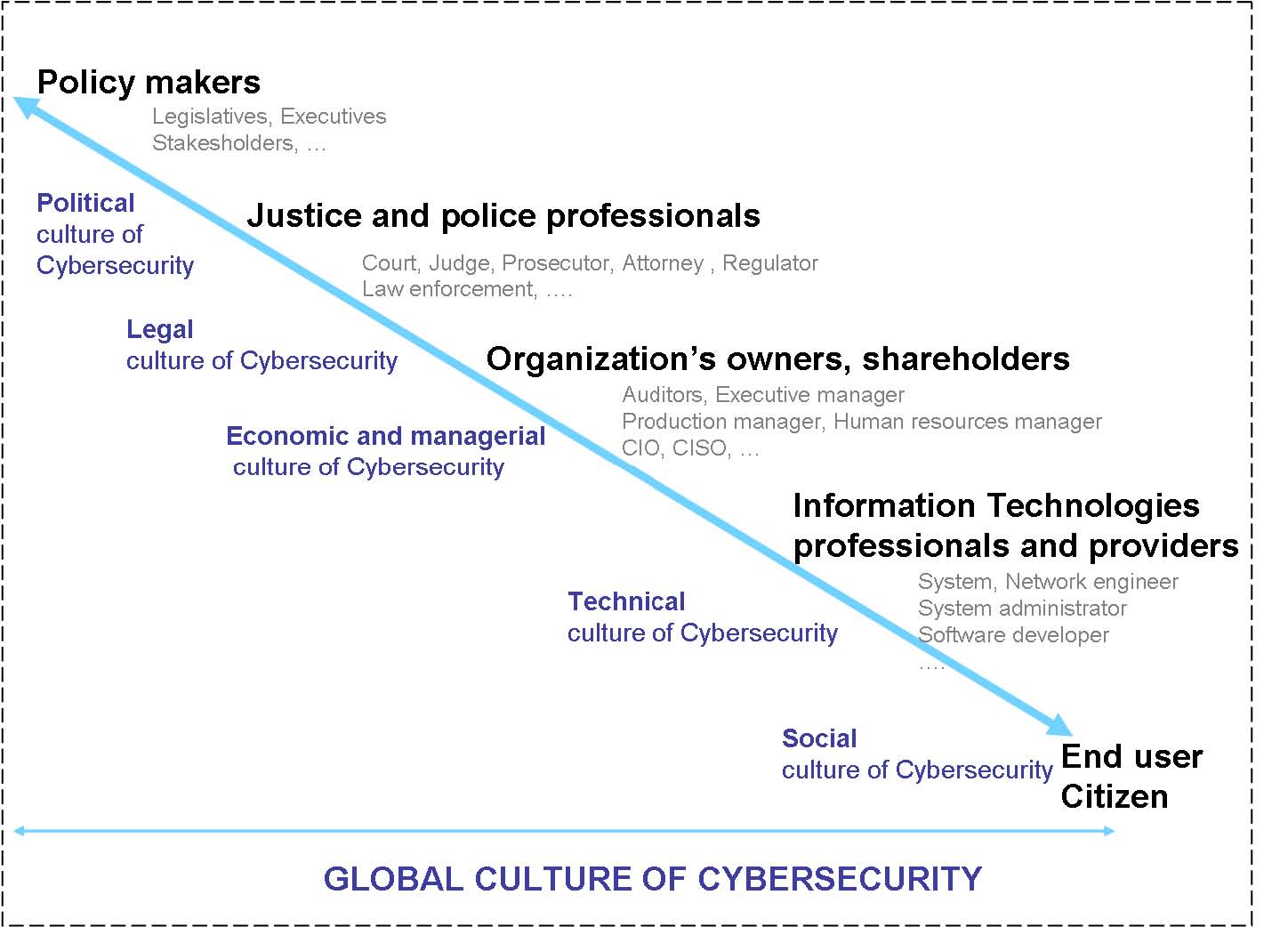

An international approach should unite many actors (as shown in Figure 5.1) belonging to the different political, legal, organizational, technical and social dimensions of cybersecurity.

Figure 5.1: From a global culture to a specific culture for actors in the information security

5.6.2 Political dimensions

Since cybersecurity and cybercrime issues are governmental, and national security, issues, governments should take account of:

• The links between social and economic development with crime and security issues in a connected society with interrelated infrastructures;

• ICT-related threats, privacy and economic crime issues;

• Needs for protection at national, regional and international levels;

• The role of relevant stakeholders and the relationship between the private and public sectors;

• How to create, maintain and develop trust in ICT environment; and

• How to develop strategic improvements in ICT security.

5.6.3. Legal dimensions

Taking into account the needs of justice and police professionals, the legal framework relating to the misuse of ICT technologies must take account of legal requirements at the national and international levels; computer investigation and forensic methodologies and tools and how to interpret and implement existing international regulation. Combating cybercrime requires a understanding of computer-related crime and of international collaboration in order to deal with global cyberthreats. Law enforcement authorities need to be able to define a legal framework of cyberlaws enforceable at national level and compatible at the international level and develop measures to fight cybercrime at an international level.

5.6.4. Organizational dimensions

Executive managers of any organization (including SMEs) should understand basic ICT security management, in particular:

• Assessments of vulnerabilities and threats;

• Security mission, management practices and conditions of success;

• How to identify valuable assets and related risks;

• How to define security policy;

• How to organize security mission and to control, evaluate, audit and estimate cost;

• How to manage security in complex and dynamic environments.

Executive managers need to create the appropriate organizational structures and procedures in order to be able to produce effective security process and master ICT-related risks and security costs and collaborate with law enforcement and technical professionals.

5.6.5. Technological dimensions

Concerning the technological dimension of cybersecurity, ICT professionals must understand ICT technical vulnerabilities and misuse, as well as ICT-related risks, cyberthreats and cyberattacks. ICT security professionals reduce the vulnerabilities of digital environment and define, design and implement efficient security tools to protect ICT infrastructure. Security technologies should be cost-effective, user-friendly, transparent, auditable and third party-controllable.

5.6.6. Social dimensions

Citizens should understand threats for end-users (virus, spam, identity usurpation, fraud, swindle, privacy offence, etc…) and their impact; understand how to adopt safe behavior online for the secure use of ICT resources; and be cybersecurity-aware.

5.7. Strategies for integration and dialogue

5.7.1. Internet Governance Forum

The Internet Governance Forum (IGF) is a multi-stakeholder forum for policy dialogue on issues relating to Internet governance. The establishment of the IGF was formally announced by the UN Secretary-General in July 2006. The mandate of the IGF is set out in Paragraph 72 of the Tunis Agenda for the Information Society. It aims to discuss public policy issues related to key elements of Internet governance in order to foster the sustainability, robustness, security, stability and development of the Internet and facilitate discourse. To date, the IGF has held two meetings, with the Third Meeting of the IGF scheduled for December 2008 in Hyderabad, India.

5.8. Initiatives by the Private Sector/Industry/Academia/Government

5.8.1. Digital Phishnet

Digital PhishNet (DPN) was established in 2004 as a collaborative enforcement body to unite industry leaders with law enforcement to combat “phishing,” a destructive and increasing form of fraud and identity theft. Phishing is a harmful online threat that involves directing people to false and misleading websites (usually through forged or “spoofed” spam mail) asking them to input their personal data, including financial information, credit card numbers and codes.

While other industry groups have focused on identifying phishing websites and sharing best practices and case information, DPN focuses on assisting criminal law enforcement in identifying and prosecuting those responsible for electronic crimes and phishing. DPN establishes a single, unified line of communication between industry and law enforcement, so critical data to fight phishing can be provided to law enforcement rapidly. Its members include ISPs, online auction sites, financial institutions, law enforcement (including participation by the FBI, Secret Service, US Postal Inspection Service, Federal Trade Commission and several Electronic Task Forces).

5.8.2. International Cyber Center

One of the recent initiatives from academia is the proposal to establish an International Cyber Center in George Mason University (GMU), Washington DC, USA. The Center will promote active partnership with public and private entities to build on existing efforts to identify and fund requirements. Funding sources include GMU support, corporate sponsorship, government and foundation funding, contracts with government and private entities, and conference, training, and exercise revenues. Sponsors are invited to participate in the advisory board and working groups.

The Center will seek to:

• Promote IT capability and infrastructure, and Internet connectivity to citizens in the developing world, consistent with security best practices, and sensitive to privacy concerns;

• Create an international collaborative framework involving key government, academic, and private sector partners to address risks to the global information infrastructure;

• Promote information security awareness by users, security professionals and providers;

• Promote cyber-defense best practices by sharing tools, procedures and policies;

• Develop state-of-the-art cyber-best practices and infrastructure;

• Develop policy frameworks for privacy and security;

• Promote capacity-building in national computer emergency response/readiness teams and incident response teams (CERT and CSIRT) and infrastructure, and information-sharing and collaboration among them;

• Carry out IT and IT security-related R&D on issues related to cyberthreats.

• Collaborate and promote information-sharing about compliance and regulatory frameworks to strengthen data privacy and computer security in the emerging world.

5.8.3. International Multilateral Partnership against Terrorism (IMPACT)

To combat cyber-terrorism, the Government of Malaysia announced in May 2006 that Malaysia would establish the world’s first truly international collaborative institution against cyber-terrorism – the International Multilateral Partnership Against Cyber Terrorism (‘IMPACT’). IMPACT is a major global public-private initiative established to respond to cyber-terrorism (such as the cyber-attacks against Estonian websites). As a not-for-profit organization, IMPACT seeks to rally efforts from governments, the private sector and academia against growing cyber-threats. It will drive collaboration among governments, industry leaders and cybersecurity experts to enhance the global capacity to respond to cyber-threats. It will have four functions:

• Training & Skills Development: IMPACT will conduct specialized training, seminars etc. for the benefit of member governments to share ‘best practices’ in protecting ICT infrastructure, identifying and closing potential vulnerabilities.

• Security Certification, Research & Development: IMPACT will develop a checklist of global best practices and international benchmarks. It may conduct security audits and o encourage member companies to embark on joint R&D with governments in specific areas.

• Global Response Centre: IMPACT will establish an emergency response centre and Early Warning System providing pro-active protection across the globe.

• Centre for Policy, Regulatory Framework & International Cooperation: Working with partners such as Interpol, EU, ITU etc., IMPACT will contribute to the development of new policies and harmonization of national laws to tackle cyberthreats.

5.8.4. North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO)

NATO plans to set up a defence centre to research and help fight cyber warfare. The Cooperative Cyber Defense Center of Excellence will operate out of Tallinn, Estonia. Cyber-warfare has been on NATO’s agenda for the past year, following the cyber-attacks against Estonia in May 2007. The attacks succeeded in knocking some financial systems off-line for several hours, prompting Estonia to ask for help from NATO. Defense ministers pressed for a NATO cyber-defense policy in October 2007, which led to the creation of the Cyber Defense Center. The centre will help NATO “defy and successfully counter the threats in this area”. The new Cyber Defense centre will be formally opened in 2009.

5.9. Strategies for multi-stakeholder partnerships

5.9.1. International Inter-Governmental

5.9.1. The Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO)

The SCO is an intergovernmental mutual-security organization which was founded in 2001 by the leaders of China, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan. In October 2007, it signed an agreement with the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), in the Tajik capital, Dushanbe, to broaden cooperation on issues such as security and crime. Given the growing importance of international information security, the SCO approved the Action Plan in the SCO framework on ensuring international information security.

5.9.2. Organization of American States (OAS)

In March 1999, the Ministers of Justice or Ministers or Attorneys General of the Americas (REMJA) recommended the Establishment of an intergovernmental expert group on cybercrime, with the mandate to:

• diagnose criminal activity targeting computers and information, or using computers as the means of committing an offense;

• diagnose national legislation, policies and practices regarding such activity;

• identify national and international entities with relevant expertise; and

• identify mechanisms of cooperation in the Inter-American system to combat cybercrime.

The Fourth Meeting of REMJA recommended that the Group of Governmental Experts on Cyber-Crime be reconvened with the mandate:

• To follow up implementation of the recommendations adopted by REMJA-III; and

• To consider the preparation of inter-American legal instruments and model legislation for strengthening hemispheric cooperation in combating cybercrime, considering standards for privacy, the protection of information, procedural aspects and crime prevention.

The OAS General Secretariat serves as the Technical Secretariat to this Group of Experts, pursuant to the resolutions of the OAS General Assembly.

5.10. International Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs)

5.10.1. London Action Plan

Global cooperation and PPPs are vital for spam enforcement, as recognized by various international fora. Building on recent efforts in organizations such as the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), EU, ITU, the OECD and the OECD Spam Task Force and the International Consumer Protection Enforcement Network (ICPEN), participants developed the London Action Plan to promote international cooperation in the fight against spam. On 11 October 2004, government and public agencies from 27 countries responsible for enforcing laws concerning spam met in London to discuss international cooperation in spam law enforcement. A range of spam enforcement agencies, including data protection agencies, telecommunications agencies and consumer protection agencies were present, including private sector representatives. Tthe Action Plan is also open to participation by interested governments, public agencies and private sector representatives, to expand the network of entities engaged in spam enforcement cooperation.

Participating government and public agencies intend to use their best efforts, in their respective areas of competence, to develop better international spam enforcement cooperation, by:

1) Designating a point of contact within their agency for further enforcement;

2) Encouraging communication and coordination between agencies with spam enforcement authority within their country to achieve efficient and effective enforcement, and to work with other Agencies within the same country to designate a primary contact for coordinating enforcement cooperation under this Action Plan.

3) Taking part in regular conference calls with other participants to discuss cases;

4) Encouraging dialogue between Agencies and private sector representatives to promote ways in which the private sector can support Agencies in bringing spam cases.

5) Prioritizing cases based on harm to victims when requesting international assistance.

6) Completing the OECD Questionnaire on cross border Enforcement of Anti-Spam Laws.

7) Encouraging and supporting the involvement of LDCs in spam enforcement cooperation.

Participating private sector representatives intend to develop PPPs against spam and to:

1) Designate spam enforcement contacts within each organization;

2) Work with other private sector representatives to establish a resource lists of individuals within particular sectors (e.g., ISPs, registrars, etc.) working on spam enforcement.

3) Participate the regular conference calls for the purpose of assisting law enforcement agencies in bringing spam cases by reporting cases of spam and new means of cooperating with agencies.

4) Work with Agencies to develop efficient and effective ways to frame information requests.

The London Action Plan reflects the mutual interest of participants in the fight against illegal spam and does not constitute legally binding obligations among participants, or a commitment to continuing participation, as cooperation is subject to national law and international obligations.

5.11. Strategies for information-sharing - Cyber Drill exercises

In March 2008. the Department of Homeland Security’s National Cyber-Security Division (NCSD) hosted Cyber Storm II, a comprehensive cybersecurity exercise, which simulated a large-scale coordinated cyber-attack on critical infrastructure sectors (including chemical, IT, communications and transportation sectors). As the Department’s biennial National Cyber Exercise, Cyber Storm II examines processes, procedures, tools and organizational responses to a multi-sector coordinated attack on global infrastructure. Exercise planning and execution strengthens cross-sector, inter-governmental and international relationships that are critical during the exercise and in actual cyber-response situations.

Cyber Storm II sought to:

• Examine the capabilities of participating organizations to prepare for, protect from, and respond to the potential effects of cyber attacks;

• Exercise strategic decision-making and interagency coordination of incident response(s) in accordance with national policy and procedures;

• Validate information-sharing relationships and communications paths for the collection and dissemination of cyber incident situational awareness, response and recovery information;

• Examine means and processes through which to share sensitive information across boundaries and sectors, without compromising proprietary or national security interests.

Cyber Storm II acted as a catalyst for assessing communications, coordination and partnerships across critical infrastructure sectors. The control center was located at a Department of Homeland Security facility in the Washington DC area. Players received “injects” via e-mail, phone, fax, in person, and exercise websites from exercise control simulating attack by persistent, fictitious adversaries with their own agenda using sophisticated attack vectors to create a large-scale incident. The scenario was developed over an 18 month planning process during which Cyber Storm II planners interacted regularly. Planners built the scenario to accommodate the objectives of the organizations and sectors participating, but not specific vulnerabilities.Participants in Cyber Storm II included the private sector, as well as federal, state and other national governments (including Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the UK). Eleven cabinet-level agencies participated in Cyber Storm II (including the Department of Defense and Department of Justice). Private sector participation was coordinated through the Information Sharing and Analysis Centers, Sector Coordinating Councils and Government Coordinating Councils. Over 40 private sector companies from the four critical infrastructure sectors participated in the exercise to simulate the interdependencies of global communication networks.

This chapter has provided an overview of some of the key challenges posed by cybercrime and other information security and network security issues and considered how these can be addressed by international cooperation. The international scope of these issues makes international dialogue and action vital. Strong and effective framework for international collaboration is needed and this chapter has given examples of promising channels and initiatives underway and in development to promote international collaboration in the field of cybersecurity.

The HLEG Work Area five has developed strategic proposals for ITU Secretary-General, in the domains of: (1) the enhancement of the focal point within ITU to manage diverse activities in collaboration with existing cybersecurity work outside ITU, and (2) involving general activities for the monitoring, coordination, harmonizing and advocating international cooperation. The recommendations arising from HLEG Work Area five are presented in Annex 1 to this book.