4.2. Capacity-building and awareness

4.3. Capacity-building and resources

4.4. Capacity-building at the global level

4.5. Capacity-building at the national level

4.6. Capacity-building at the end-user level

4.7. Capacity-building for an inclusive society

Modern communication systems are characterized by growing digital content, generalized mobility and a greater capacity to transfer more data than ever before. As usage and bandwidth have risen, so too has the potential of users to inflict damage. Incidents of cybercrime range from the highly-publicized cyber-attacks that almost succeeded in shutting down the Internet in Estonia in April-May 2007 to everyday incidents of cybercrime on a smaller scale – for example, when goods are ordered online, but not delivered, or when people cannot pay for goods and services safely and securely. As the scale of cybercrime rises, consumer trust suffers and countries could face growing challenges, as their economies are either negatively impacted or the online economy fails to grow to its full potential.

The best guarantee for cybersecurity is the development of a reliable cyber-culture, with established norms of behavior that users follow voluntarily. However, such a cyber-culture has to be nurtured. One cannot hope that the benign community codes of conduct that early users of the Internet adopted in their excitement over the possibilities of the new communications medium will be automatically followed, as the Internet expands. Useful guides in this area are the UN General Assembly Resolution 57/239 on the Creation of a Global Culture of Cybersecurity and the OECD’s Guidelines for the Security of Information Systems and Networks.

It is the prerogative of sovereign states to create legal regimes governing their jurisdictions and to sign up to international regulatory regimes. Sovereign states also command the resources needed to address these issues. However, resources are unequally distributed and countries need to prioritize resources to support cybersecurity. Cybersecurity needs the development of a cyber-culture and acceptable user behavior in the new reality of cyberspace, but it is also based on norms of correct behavior and the capacity to pursue wrong-doers and bring them to justice, albeit in the online world. The need to deter cybercrime and prosecute wrong-doers is universal, even for countries with low Internet access rates. However, countries’ capacity to promote cybersecurity is uneven and countries must build capacity to address these issues.

There is only limited authority to impose laws on the borderless environment of the Internet, so improving security is only possible through voluntary collective action. This chapter considers capacity-building from both the national and international perspective, in terms of the main actors, their main activities and how to improve national capacity to promote cybersecurity.

4.2. Capacity-building and awareness

Considerable work has been carried out in capacity-building for development by various institutions, including United Nations development programmes and the World Bank. In cybersecurity, the main agents are the nation states. However, capacity-building to promote cybersecurity is complex, for several reasons. Cybersecurity has long been considered as a technical field, belonging to specialized agencies. Furthermore, global connectivity and instant communications mean that countries have to initiate actions to promote cybersecurity at the national level.

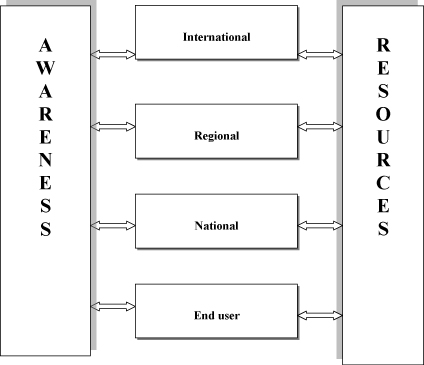

Awareness-raising and the availability of resources are cross-cutting issues that need to be dealt with separately. A capacity-building framework for promoting cybersecurity is represented schematically in Figure 4.1.

Mechanisms for awareness-raising certainly vary between countries, as do needs and methods. The leading role is often taken by non-governmental organizations, but government and the private sector also have important roles. For governments, building a culture of cybersecurity includes incorporating safe online behavior lessons into school curricula. Many countries have in fact already done this.

The private sector can also take the initiative. In Estonia, the private sector (e.g., the financial sector and telecommunication operators) decided that a safer Internet would directly benefit their business. In 2006, they established the ambitious goal of becoming the most cyber-secure nation by 2009, and launched an awareness campaign, dedicated website and projects using Public Key Infrastructure and digital ID cards, that were already in use by the government.

For awareness campaigns to be effective, it is vital that decision-makers are fully informed, in order to become champions for the cause. This is best accomplished by educating decision-makers and by keeping cybersecurity in the news. For example, the awareness created by Y2K campaign could be a good illustration for the kind of publicity needed to promote cybersecurity. Awareness campaigns should also educate key decision-makers in government.

Training programmes should be made available in establishing cybersecurity policy, organizational frameworks and technical solutions. Such training workshops should promote the exchange of information between security specialists and create the necessary expertise at the policy-making level to advance cybersecurity onto the domestic policy agenda.

Awareness-raising is a vital part of establishing capacity for national governments in cybersecurity and to help ensure the functioning of a sustainable framework for international cooperation. To raise awareness of cybersecurity issues, policy-makers and other stakeholders in cybersecurity could:

• Establish public-private partnerships, when required;

• Undertake widespread publicity campaigns to reach as many people as possible;

• Make use of NGOs, institutions, banks, ISPs, libraries, local trade organizations, community centers, computer stores, community colleges and adult education programmes, schools and parent-teacher organizations to get the message across about safe cyber-behaviour online.

Countries should also build capacity to:

• Develop an effective legal framework enforceable at the national level and compatible at the international level (to answer the needs identified in Work Area 1 in Chapter 1);

• Promote the adoption of technical and procedural cybersecurity measures (Chapter 2);

• Put in place organizational structures (Chapter 3);

• Support national, regional, international cooperation (Chapter 5);

• Empower end-users to adopt safe behavior online to be responsible cyber-citizens;

• Train and educate all actors of the information society. Security awareness programmes could be tailored to targeted audiences (children, the elderly, large firms or SMEs, etc.).

Several significant initiatives already exist to raise cybersecurity awareness and promote training (for example, ENISA ). Ongoing efforts by both private and public sector organizations, as well as non-profit associations, should continue to be supported.

4.3. Capacity-building and resources

Building and maintaining cybersecurity requires resources. Given the borderless nature of the Internet, even the most powerful and well-resourced countries cannot safeguard cybersecurity alone, so international cooperation is in every country’s interest (despite inevitable differences in the political and legal cultures between countries).

The ITU has undertaken a significant leading initiative in international cooperation to promote cybersecurity by launching the Global Cybersecurity Agenda (GCA). At the same time, no single organization can provide international cybersecurity for the entire world. ITU can play an important role as a repository of knowledge and a global facilitator of overall efforts for a safer Internet. In addition to general global resource centers, regional centers could be built up and integrated into the overall cybersecurity coordination network.

Countries’ willingness to spend on cybersecurity promotion varies, according to perceived threat levels. At a time when actual threats are constantly evolving, the financial resources needed to build and disseminate collective know-how require long-term commitment from donors.

4.4. Capacity-building at the global level

As cyberspace has few boundaries, one example of a major initiative building capacity at the global level is the Global Cybersecurity Agenda of the ITU. The ITU was entrusted by the World Summit of the Information Society (WSIS) as sole Facilitator/Moderator with responsibility for WSIS Action Line C5, “Building Confidence and Security in the use of ICTs”. The ITU launched the GCA as the framework for its work in WSIS Action Line C5.

There are a number of global actors that can support the work of the GCA, including:

• International organizations;

• Business actors; and

• Non-governmental organizations.

The number of organizations that will prioritize cybersecurity on their main agenda will grow, as cybersecurity becomes more important. Another pioneer working in this area was a regional organization, the Council of Europe, which initiated the creation of the Convention on Cybercrime.

4.5. Capacity-building at the national level

National capacity-building is vital to promote cybersecurity on the global agenda. Law enforcement operates within the framework of nation states, so wrong-doers can be pursued and punished. Within each nation state, cybersecurity can be promoted by taking steps to protect critical information infrastructure and services for the safety of citizens, firm competitiveness and state sovereignty.

Everyone dealing with ICT devices, tools or services is concerned by cybercrime and other information security and network security issues, including governmental institutions, large and small firms, and other organizations and individuals. Security approaches are often limited to risk management and the adoption of measures to reduce risk and protect the IT resources of large organizations. However, security approaches must also meet the security needs of SMEs and individuals, as people are the weakest link in any security chain.

Cybersecurity includes topics related to cybercrime and the misuse of ICTs, but it also requires that technologies should be less vulnerable (see Chapter 2). Cybersecurity also involves the development of reliable and safe behavior with regards to the use of ICTs. It is essential that stakeholders in cybersecurity work in partnership with IT service and content providers to improve the security of their products and services. The public and private sectors should work together to ensure that products and services include simple, yet flexible security measures and mechanisms. Products should be well-documented and comprehensive and security mechanisms should be readily understood and configured easily by untrained users (See Chapter 2). Partnerships between the public and private sectors should help ensure that security is integrated at the beginning of information technologies’ infrastructure development life cycle.

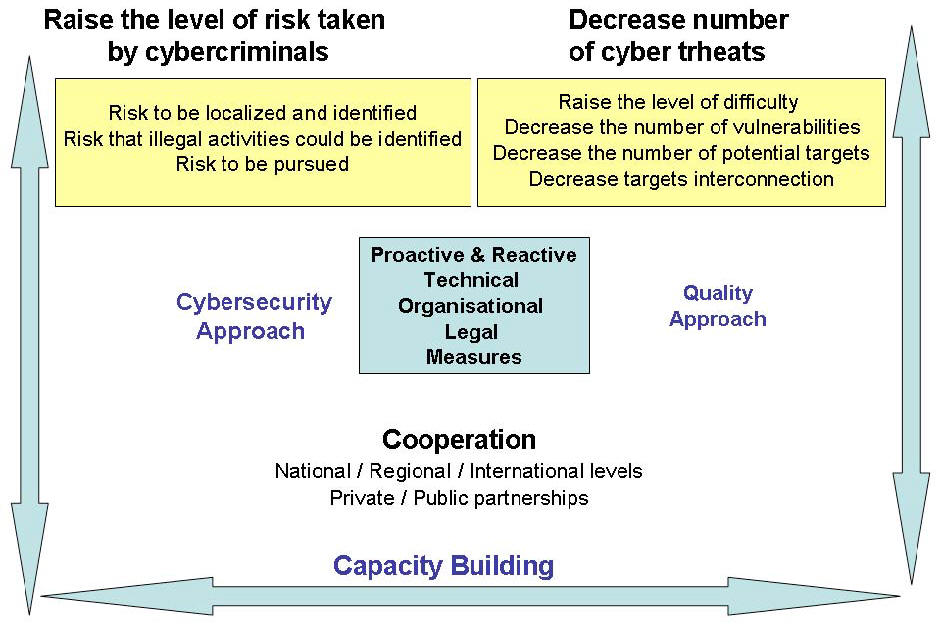

Capacity-building to promote cybersecurity should take into account the role of different stakeholders (including their motivation, inter-linkages and interactions). As with CSIRTs (Chapter 3), the generic functions of security can be classified into pro-active and reactive measures (Figure 4.2).

Figure 4.2: Generic cybersecurity functions

Pro-active measures to promote cybersecurity include intelligence gathering, data collection and analysis in order to understand the issues at stake and to design preventive actions avoiding and limiting the damage caused by cybercriminals. Both pro-active and preventive actions rely on secure and reliable ICTs and management procedures. Reactive measures include crisis management and recovery actions.

Awareness programmes can help build national capacity to promote cybersecurity. Eucational programmes should be tailored to different audiences (e.g. youth and older people, professionals etc.). Awareness campaigns and strong laws against cybercrime can help raise the risks perceived by criminals and make the prosecution of offenses enforceable and effective (see Chapter 1).

A global strategy to promote cybersecurity can be enhanced by Increasing the level of perceived risks and increasing the level of effort criminals have to make to perpetrate a crime. Improved technical and procedural measures (Chapter 2) can help make cybercrime more difficult to achieve. Effective legal measures (covered in Chapter 1), as well as more effective organizational structures (Chapter 3), in conjunction with greater international cooperation (Chapter 5), can help raise the level of risks perceived by criminals. The illicit profits possible through cybercrime have to be minimized to make criminal offenses less profitable vis a vis the level of skill required and the level of risk. Effective capacity-building can help raise levels of risk taken by cybercriminals, including risks of being identified, located, pursued and prosecuted. Effective capacity-building measures (Figure 4.3) can also help reduce vulnerabilities and reduce the number of potential targets and their interconnectivity.

Achieving these goals would help create a digital environment that is more difficult to attack. Capacity-building measures are pro-active actions that require a good understanding of ICT-related risks; complementary technical, legal and organizational measures and effective international cooperation.

Figure 4.3 Cybersecurity capacity-building

Cybersecurity is a driving force for the economic development of regions and must be incorporated into the roll-out of ICT infrastructure. Security needs need to be addressed at the same time as ICT development - the digital divide should not be exacerbated by a security divide. The international security chain is only as strong as its weakest link, which affects overall levels of global cybersecurity. Individuals should remain at the heart of ICT security, to realize an inclusive information society of fully aware consumers. Technological or legal solutions cannot fully compensate for design or management errors.

4.6. Capacity-building at the end-user level

Minimum awareness and ‘safety’ requirements are needed at the end-user level. The basic principles of cybersafety and safe behaviour online should be included in basic computer courses, when people start to learn about the use of ICTs. In particular, end-users need to be educated about boundaries between personal privacy and online identity. Current existing regulations are outdated by technological developments, especially by WEB2.0 social software, and while societies readjust, it is vital to teach safe online behavior early on. In this respect, initiatives such as the computer driver’s license could help with software usage know-how.

The rapid expansion of the user base does not originate solely with the younger generation. All social strata and age groups are learning to use different networked ICT applications and are thus exposed to the threats, as well as benefits, of the virtual world. As more societies move to embrace electronic commerce, banking and other applications, cyberthreats are diversifying and growing rapidly. To counter these tendencies needs concerted effort by all agents, especially by governments, non-governmental organizations and the private sector. Incentives should be provided for cybersafety initiatives by national governments, as vital components of an awareness-raising strategy to promote cybersecurity.

4.7. Capacity-building for an inclusive society

ITU Study Group Q.22/1 Report on best practices for a national approach to cybersecurity offers an extensive management framework for organizing national cybersecurity efforts: “Considering that personal computers are becoming ever more powerful, that technologies are converging, that the use of ICTs is becoming more and more widespread, and that connections across national borders are increasing, all participants who develop, own, provide, manage, service and use information networks must understand cybersecurity issues and take action appropriate to their roles to protect networks. Government must take a leadership role in bringing about a culture of cybersecurity and in supporting the efforts of other participants”. Promoting a national culture of cybersecurity is an integral element of the management framework for organizing national cybersecurity efforts.

4.7.1. Creation of a national Culture of Security

1. The promotion of a national culture of security addresses not only the role of government in securing the operation and use of information infrastructures (including government operated systems), but also outreach to the private sector, civil society and individuals. This element also covers training of users of government and private systems, future improvements in security, and other significant issues, including privacy, spam and malware.

2. According to an OECD study, the key drivers for a culture of security at the national level are e-government applications and services, and protection of national critical information infrastructures. As a result, national administrations should implement e-government applications and services to improve their internal operations, as well as to provide better services to the private sector and citizens. The security of information systems and networks should be addressed not only from a technological perspective, but should also include risk prevention, risk management and user awareness. The OECD found that the beneficial impact of e-government activities extends beyond public administration, to the private sector and individuals. E-government plays a key role in fostering the diffusion of a culture of security.

3. Countries should adopt a multidisciplinary and multi-stakeholder approach to promoting cybersecurity. Some countries are establishing a high-level governance structure for the implementation of national policies. Awareness-raising and education initiatives are very important, along with the sharing of best practices, collaboration among participants and the use of international standards.

4. International cooperation is extremely important in fostering a culture of security, along with the role of regional fora to facilitate interactions and exchanges.

4.7.2. Specific Steps to Promote a Culture of Cybersecurity

4.7.2.1. Implement a cybersecurity plan for government-operated systems.

The initial step to secure government-operated systems is the development and implementation of a security plan. Preparation of this security plan should address risk management, as well as security design and implementation. Periodically, both the plan and its implementation should be reassessed to measure progress and to identify areas where improvement is needed. The plan should include provisions for incident management, including response, watch, warning and recovery, as well as information-sharing. The security plan should also address training of users of government systems and collaboration among government, industry and civil society on security training and initiatives.

4.7.2.2. Security awareness programmes and initiatives for users of systems and networks

An effective national cybersecurity awareness programme should promote cybersecurity awareness among the public and key stakeholders, maintain relationships with cybersecurity professionals to share information about cybersecurity initiatives, and promote collaboration on cybersecurity issues.

Three functional components need to be considered, in developing an awareness programme:

(1) stakeholder outreach and engagement to build and maintain trusted relationships between industry, government and academia to raise cybersecurity awareness;

(2) coordination and collaboration on cybersecurity activities across the government; and

(3) communications, with both internal and external communications (e.g. other government agencies, industry, educational institutions, home computer users, and general public).

4.7.2.3. Encourage the development of a culture of security in firms

Developing a culture of security in private sector firms can be achieved in several ways. Many government initiatives have been directed at awareness-raising for SMEs. Government dialogue with business associations or government-industry collaboration can help administrations design and implement education and training initiatives. Examples of such initiatives include: making information available off-line and online (e.g. booklets, manuals, handbooks, model policies and concepts); setting up websites targeting SMEs and other specific stakeholders; provision of training; provision of an online self-assessment tool; and offering financial assistance and tax support or other incentives for fostering the production of secure systems or taking proactive steps towards enhancing cybersecurity.

4.7.2.4. Support outreach to civil society

Some governments have cooperated with the private sector to raise citizens’ awareness of cyber-threats and measures that should be taken to counter them. Some countries organize specific events, with activities to promote information security to a broad audience. Most initiatives aim to educate children and students either through school, or by the direct distribution of guidance material. The support material used varies from websites, games, and online tools, to postcards, textbooks and diplomas. Examples of such initiatives include: training courses for parents to inform them about security risks; providing support material for teachers; providing children with online tools; and developing textbooks and games. Government and the private sector can share the lessons they have learned in developing security plans and training users, learn from others’ successes and innovations and work to improve the security of domestic information infrastructures.

4.7.2.5. Promote a comprehensive national awareness programme

Many information system vulnerabilities exist because of a lack of cybersecurity awareness on the part of users – whether these are system administrators, technology developers, procurement officials, auditors, chief information officers or corporate boards. These vulnerabilities can jeopardize the infrastructure, even if they are not actually a part of the infrastructure itself. For example, the security awareness of system administrators is often a weak spot in an enterprise security plan. Promoting industry efforts to train personnel and adopt widely-accepted security certifications for personnel will help reduce these vulnerabilities. Government coordination of national outreach and awareness activities to enable a culture of security will also build trust with the private sector. Cybersecurity is a shared responsibility. Portals and websites can be a useful mechanism to promote a national awareness programme, enabling government agencies, businesses, and individual consumers to obtain relevant information and carry out measures that will protect their portions of cyberspace.

4.7.2.6. Enhance Science and Technology (S&T) and Research and Development (R&D) activities.

To the extent that government supports R&D activities, some of its efforts should be directed towards the security of information infrastructures. Through the identification of R&D priorities to mitigate cyberthreats, countries can help shape the development of products with security features built-in, as well as addressing difficult technical challenges. Where R&D is conducted in an academic institution, there may be opportunities to engage students in cybersecurity initiatives. 4.2.7.7 Review existing privacy regime and update it to the online environment.

This review should consider privacy mechanisms adopted by various countries, and by international organizations, such as the OECD. The OECD Guidelines on the Protection of Privacy and Transborder Flows of Personal Data , adopted on 23 September 1980, represent one form of international consensus on general guidance concerning the collection and management of personal information. By setting out core principles, these guidelines play a major role in assisting governments, business and consumer representatives in their efforts to protect privacy and personal data, and in obviating unnecessary restrictions to transborder data flows, both online and off-line.

4.7.2.8. Develop awareness of cyber-threats and available solutions.

Addressing technical issues requires that governments, businesses, civil society and individual users work together to develop and implement measures that incorporate technological (i.e., standards), process (e.g., voluntary guidelines or mandatory regulations) and personnel (i.e., best practices) components.

4.8.1. Government systems and networks (4.2.7.1, 4.2.7.2, 4.2.7.7)

• UNGA RES 57/239 Annexes a and b. www.un.org/Depts/dhl/resguide/r57.htm

• OECD “Guidelines for the Security of Information Systems and Networks: Towards a Culture of Security” [2002] www.oecd.org/document/42/0,2340,en_2649_34255_15582250_1_1_1_1,00.html

• OECD Ministerial Declaration on the Protection of Privacy on Global Networks (1998) The Promotion of A Culture of Security for Information Systems and Networks in OECD Countries (DSTI/ICCP/REG(2005)1/Final.

• Multi State Information Sharing and Analysis Center: Main Page: www.msisac.org/

• The U.S. Federal Information Security Management Act of 2002 (FISMA) csrc.nist.gov/policies/FISMA-final.pdf

• U.S. HSPD-7, “Critical Infrastructure Identification, Prioritization and Protection” www.whitehouse.gov/news/releases/2003/12/20031217-5.html

• U.S. Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR), parts 1,2,7,11, and 39. www.acqnet.gov/FAR/

• The [U.S.] National Strategy to Secure Cyberspace: www.whitehouse.gov/pcipb/

• U.S. CERT site: www.us-cert.gov/

• U.S. NIST site: csrc.nist.gov/ and csrc.nist.gov/fasp/ and csrc.nist.gov/ispab/

4.8.2. Business and private sector organizations (4.7.2.3, 4.7.2.5, 4.7.2.7)

• National Cyber Security Partnership: www.cyberpartnership.org

• U.S. CERT: www.us-cert.gov/

• U.S. DHS/Industry “Cyber Storm” exercises: www.dhs.gov/xnews/releases/pr_1158340980371.shtm

• U.S. DHS R&D Plan: www.dhs.gov/xres/programs

• U.S. Federal Plan for R&D: www.nitrd.gov/pubs/csia/FederalPlan_CSIA_RnD.pdf

• U.S. President’s Information Technology Advisory Committee report on Cyber Security research priorities: www.nitrd.gov/pitac/reports/20050301_cybersecurity/cybersecurity.pdf

4.8.3. Individuals and civil society (4.7.2.4, 4.7.2.6, 4.7.2.7)

• Stay Safe Online: www.staysafeonline.info/

• OnGuard Online: onguardonline.gov/index.html

• U.S. CERT: www.us-cert.gov/nav/nt01/

• OECD’s Anti-Spam toolkit, www.oecd-antispam.org

• See also: The OECD questionnaire on implementation of a Culture of Security (which is found at DSTI/ICCP/REG(2004)4/Final) and the U.S. response to the questionnaire (which is found at webdomino1.oecd.org/COMNET/STI/IccpSecu.nsf?OpenDatabase). The U.S. response provides a comprehensive overview of U.S. efforts in this area.

• New Zealand: www.netsafe.org.nz

• Canada: www.psepc-sppcc.gc.ca