3.2. Organizational Structures and Policies for Cybersecurity

3.3. A Framework for Organizational Structures

3.4. Global framework for watch, warning and incident response

The World Summit on the Information Society (WSIS) acknowledged the role of confidence and security in the use of ICTs as one of the main pillars in building an inclusive, secure and global information society. The global challenges to cybersecurity and information security and network security issues can only be addressed with a strategy uniting key stakeholders in a framework of international cooperation.

The ITU Secretary-General seeks to “create a secure and high-trust information society for all nations where all participants of the global information society can reap the benefits of ICTs and avoid the dangers and pitfalls”. On 17 May 2007, the ITU launched the Global Cybersecurity Agenda (GCA) as an international framework for international cooperation seeking to building confidence and security in the information society. The GCA unites existing ITU activities, work done or in progress in ITU-T, ITU-R and ITU-D. The GCA builds on existing national, regional and international initiatives to avoid duplication of work and encourage collaboration with all relevant partners.

This chapter on Organizational Structures considers the creation of effective organizational structures for combating cybercrime and the role of watch, warning and incident response to ensure cross-border coordination between new and existing initiatives. In designing their national strategy for cybersecurity, it is vital that countries take into account the role of different stakeholders, as the public or private sector alone cannot secure cyberspace. Governments balance the interests of public sector, business and citizens/consumers in policy, legal and regulatory issues, standards and public awareness. They are ultimately responsible for the maintenance of law and order within their jurisdictions and can take a leadership role in building confidence and security in the use of ICTs.

The private sector also has a vital role to play, as it has developed substantial know-how in how to deal with cyber-incidents and researches and develops innovative technical solutions. Following privatization of the utility sector in many countries, the private sector often operates critical infrastructure. It can take the lead in developing cost-effective security technologies; adopting vital measures to mitigate vulnerabilities (Chapter 2); and cooperating with law enforcement authorities.

Universities fund research in cybersecurity and develop solutions based on new understanding and technologies (e.g. academic researchers have developed many key security algorithms used to encrypt confidential data exchange and online transactions). They often engage in industry-academia-government cooperation and host conferences and publish articles essential for exchanging knowledge and latest research findings.

Finally, consumer groups, trade associations and non-profit organizations also have a key role to play in helping citizens understand that they are part of a far larger “security chain”. Users need to develop correct and ethical behaviour online in order to protect their safety and their values, including investing in firewalls and regular virus updates and checking for security alerts. Civil society plays a vital role in consumer protection and in promoting cybersecurity awareness, tools and practices.

Taking into account the roles of different stakeholders, this chapter considers the creation of effective organizational structures for cybercrime and examines the role of watch, warning and incident response to promote international coordination. It proposes that countries should take into account the main recommendations in the ISO/IEC 27000 family of information security standards, which provide good practice guidance on Information Security Management Systems to protect the confidentiality, integrity and availability of digital information and information systems.

3.2. Organizational Structures and Policies for Cybersecurity

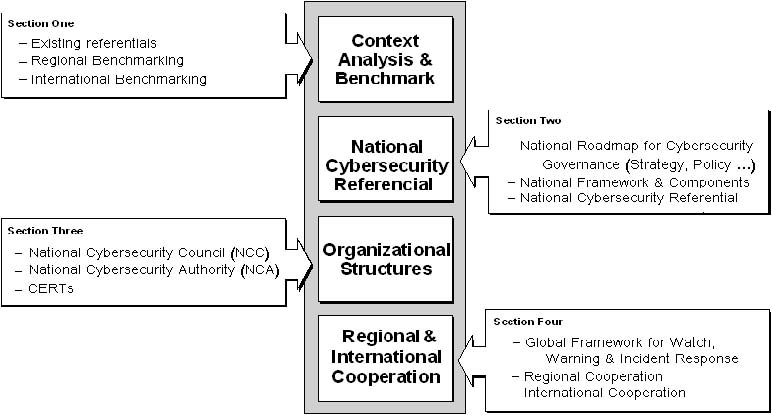

This chapter proposes an approach to the development of effective organizational structures to promote cybersecurity and maintain resilient and reliable information infrastructure. This approach has four main stages (Figure 3.1):

Figure 3.1: An Approach to Organizational Structures for Cybersecurity

3.2.1. The Role of Benchmarking

Countries should first research and analyze their specific circumstances and their key challenges, information security and network security issues, through regional and international benchmarking. The development of a policy to promote cybersecurity is recognized as a top priority by many countries, including developing countries. A national strategy for Security of Network and Information Systems should maintain resilient and reliable information infrastructure and aim to:

1. Ensure the safety of citizens;

2. Protect the material and intellectual assets of citizens, organizations and the State;

3. Prevent cyber-attacks against critical infrastructures;

4. Minimize damage and recovery times from cyber-attacks.

A benchmarking exercise of different countries’ national strategies for cybersecurity reveals that national cybersecurity strategy experiences differ greatly - some countries have set up permanent committees to address cybersecurity, others have launched working groups, while others have established advisory councils or have a cross-disciplinary centre. While many countries have established national agencies and watch and warning systems and incident response, and have put in place the organizational structures needed for coordinating responses to cyber-attacks, other countries have yet to establish such structures. It is difficult for developing countries to match the capacity of developed countries, due to lack of resources and expertise.

Many developed countries have already established a strategy for national cybersecurity and have developed policies to meet their national objectives and commitment to national security. Some countries such have integrated cybersecurity into their national ICT strategy, prioritizing cybersecurity as an essential pillar of the information society. The experience of other countries can help countries in developing their national cybersecurity strategy. Countries that have already developed successful National Plans for the Protection of Information Infrastructures can share best practices with others.

3.2.2. National Roadmap for Governance in Cybersecurity

Countries can develop a roadmap for governance in cybersecurity, by establishing a national strategy and policy for cybersecurity, identifying key stakeholders and promoting a culture of cybersecurity. Governments have a major leadership role to play in:

• Establishing clear responsibility for cybersecurity at all levels of government (local, regional and federal or national), with clearly defined roles and responsibilities;

• Making a clear commitment to cybersecurity, which is public and transparent;

• Encouraging private sector involvement and partnership in government-led initiatives to promote cybersecurity.

The development of a national policy framework is a top priority in developing high-level governance for cybersecurity. The national policy framework must take into account the needs of national critical information infrastructure protection. It should also seek to foster information-sharing within the public sector, and also between the public and private sectors. Private and public sector cooperation is effective in promoting cybersecurity, as it makes use of private sector expertise and experience.

Cybersecurity governance should be built on a National Framework addressing challenges and other information security and network security issues at the national level, which could include:

• National strategy and policy;

• Legal foundations for transposing security laws into networked and online environments;

• Involvement of all stakeholders;

• Developing a culture for cybersecurity;

• Procedures for addressing ICT security breaches and incident-handling (reporting, information sharing, alerts management, justice and police collaboration);

• Effective implementation of the national cybersecurity policy;

• Cybersecurity programme control, evaluation, validation and optimization.

A national strategy to promote cybersecurity issue is vital for national security, citizens’ safety and the nation’s economic welfare. Different stakeholders (government authorities, the private sector, citizens and users) should be aware of their roles in contributing to the prevention of, preparation for, response to, and recovery from incidents. The national strategy should be linked with the national legal framework, to ensure that it is properly grounded in law and laws may need to be updated to ensure that they address different types of cybercrime (Chapter One).

3.3. A Framework for Organizational Structures

It is duty of the state to protect the national digital heritage, critical infrastructures and sustain economic development, as well as safety of its citizens. The following sections propose an organizational framework to facilitate the establishment of organizational entities that could help promote cybersecurity and protect critical infrastructure (Figure 3.2). Three kinds of organizational structures are proposed to promote cybersecurity and address cybercrime and other information security and network security issues:

1. A National Cybersecurity Council (NCC);

2. A National Cybersecurity Authority (NCA); and

3. A National CERT and/or CSIRTs.

These organizational structures may already exist in some countries, sometimes under other names. These structures need to be adapted with regards to the availability of resources, private/public partnerships and ICT development of each country. Each country has to define its own relevant structures, with specific allocated roles, functions and resources. For each country, it is recommended that a central focal point or specific organizational entity be established to support a national cybersecurity policy and facilitate regional and international cooperation. Countries may wish to establish a National Cybersecurity Council (NCC). Depending on the size and needs of the country, several alternative organizational structures could be designed.

Figure 3.2: A framework for organizational structures

3.3.1. National Cybersecurity Council (NCC)

National governments should establish an entity to formalize and coordinate its cybersecurity efforts. Different countries will choose different models, and all models should involve a close partnership with the private sector. For the purposes of this Chapter, this focal point is referred to as the National Cybersecurity Council (NCC). The NCC could be a specific (separate) entity or a component of an existing National Security Council. This NCC should be a national leader structure for coordination and adoption of cybersecurity measures, in:

• defining national cybersecurity policies;

• setting priorities for national cybersecurity initiatives;

• coordinating cybersecurity actions at the national level;

• identifying stakeholders and public-private relationships to address cybersecurity issues;

• collaborating with several governmental services or agencies such as intelligence service, secret service, security bureau, police forces, High-Tech Crime Unit,

• collaborating with regional or international agencies (such as Europol or Interpol);

• monitoring governmental ICT systems and infrastructures;

• coordinating actions and development of digital identity systems and management and good practices related to digital identities, among others.

In order to ensure the implementation of the national strategy, the NCC should be linked to top-level government authority and integrated with existing structures. The NCC could rely on other organizational structures, including the national CERT (or equivalent institution).

3.3.2. National Cybersecurity Authority (NCA)

In some cases, it may also be effective to set up a National Cybersecurity Authority (NCA) to implement cybersecurity goals. The NCA would facilitate the measures identified in the national policy defined by the National Cybersecurity Council. In order to guarantee separation between the definition of policy and its implementation, the NCA must have a degree of independence to avoid interference. In addition, other functions (such as compliance verification, risk audits and security evaluation) could be offered by NCA.

The NCA will assist NCC in all its operational activities and help organize exercises to help industry test their emergency plans. The NCA could work with industry to establish goals and guidelines for the security of ICT infrastructure and services. The NCA could also contribute to the application of international standards relating to cybersecurity and the accreditation or certification of ICT infrastructures, services or providers.

3.3.3. National Computer Emergency Response Team (CERT)[1]

The formation of dedicated information security teams within different organizations - firms, academic institutions, governmental agencies or at the national level - can help protect countries’ information assets and maximize returns on investments in IT infrastructure. A Computer Emergency Response Team (CERT) is an organization that monitors computer and network security to provide and coordinate incident response services to victims of attacks. It also publishes alerts concerning vulnerabilities and threats and may offer other information to help improve computer and network security. Today, there are at least 250 “official” ones and this number is growing rapidly all the time.

A national CERT or Computer Security & Incident Response Team (CSIRT) [2] is an organization which represents a government’s information infrastructure protection, or in some cases, a point for national coordination of responses to ICT security threats. CSIRTs deliver many services. Figure 3.3 gives an overview of CSIRT services (as defined in the “Handbook for CSIRTs” published by the CERT/CC). Fundamental services appear in bold font. A distinction is made between reactive and proactive services. Proactive services seek to prevent incidents mainly through awareness, information-sharing, security tools deployment and training, while reactive services deal with the handling of incidents and mitigating resulting damage.

Figure 3.3: The main services provided by CERTs/CSIRTs

|

Reactive Services |

Proactive Services |

Artifact Handling |

|

• Alerts and Warnings • Incident Handling • Incident analysis • Incident response support • Incident response coordination • Incident response on site • Vulnerability Handling • Vulnerability analysis • Vulnerability response • Vulnerability response coordination ® ENISA |

• Announcements • Technology Watch • Security Audits or Assessments • Configuration and Maintenance of Security • Development of Security Tools • Intrusion Detection Services • Security-Related Information Dissemination |

• Artifact analysis • Artifact response • Artifact response coordination |

|

Security Quality Management |

||

|

• Risk Analysis • Business Continuity and Disaster Recovery • Security Consulting • Awareness Building • Education/Training • Product Evaluation or Certification |

CSIRTs vary dramatically in the services they provide and the constituents they serve. Some are CSIRTs with national responsibility. Most CSIRTs belong to private organizations and are established to fulfill specific functions, depending on their situation. Their mandate, services, constituents, activity, size and structure all vary widely. Many owe their status to the fact they are members of the Forum for Incident Security and Response Teams (FIRST). One key function that all CERTs share is that they should be able to provide timely information about the latest relevant threats and to provide assistance in incident response when needed. The cyberthreat environment is evolving relentlessly and CSIRTs need to keep abreast of these changes, making it even more essential that different CSIRTs find ways to share as much information as possible.

National CSIRTs almost always assume responsibilities for readiness and response to large-scale attacks. For example, the main mission of US-CERT is to protect US critical infrastructures. US-CERT has organized major international exercises (e.g. “Cyberstorm”, involving Australia, New Zealand, and Canada), simulating large-scale attacks on critical sectors. APCERT also organizes a drill every year along similar lines, to test the ability of CSIRTs from different countries to cooperatively respond to large-scale contingencies. In early 2007, CERT/CC published a list of some 40 CERTs recognized as having “national” responsibilities.[3] If countries do not yet have a CERT/CSIRT, they could be encouraged to establish one.

CERTs often also undertake “watch, warning, incident response and recovery” for ICT-related incidents. This focal point would also provide up-to-date and free information over dedicated communication channels (e.g., e-security web portals, email distribution list) on cyber-threats, cyber-risks and alerts, as well as good practices. A multilingual information-sharing and alert system should be established to link together existing or planned national public and private initiatives. Outreach campaigns could reach a large part of the population through a combination of advertisements, partnering with ISPs and providers of ICT security solutions. Awareness campaigns could make use of websites and portals, seminars directed at general IT users and system administrators, training, brochures and workshops. Some countries have laws requiring firms to evaluate information security through risk audits. Awareness campaigns should also be tailored to specific audiences - a one-size-fits-all strategy might be easier to develop, but it is far less effective.

The ITU-D’s ICT Applications and Cybersecurity Division website provides a wealth of information about CERTs, CSIRTs and Warning, Advice and Reporting Points (WARPs). ITU-D has developed detailed research reports on key activities for addressing cybersecurity at the national level, about preparations for, the detection, management and responding to cyber-incidents through the establishment of watch, warning and incident response capabilities. Effective incident management requires consideration of funding, human resources, training, technological capability, government and private sector relationships, and legal requirements. Collaboration at all levels of government and with the private sector, academia, regional and international organizations, is necessary to raise awareness of potential attacks and steps toward remediation.

These CERT/ CSIRT resources include:

• Incident Management Capability Metrics Version 0.1 (pdf)

• Creating a Computer Security Incident Response Team: A Process for Getting Started

• Action List for Developing a Computer Security Incident Response Team (CSIRT)

• Steps for Creating National CSIRTs (pdf)

• Defining Incident Management Processes for CSIRTs: A Work in Progress (pdf)

• Staffing Your Computer Security Incident Response Team – What Basic Skills Are Needed?

• Handbook for Computer Security Incident Response Teams (CSIRTs) (pdf)

• Organizational Models for Computer Security Incident Response Teams (pdf) | html

• State of the Practice of Computer Security Incident Response Teams (pdf) | html

• CSIRT Frequently Asked Questions

• Security vulnerabilities and fixes

• CERT/CC Virtual Training Environment (VTE).

In addition to reactive services, such as incident response, CSIRTs and CERTs nowadays also often provide their customers with a variety of other security services, including alerts and warnings, advisories, technical assistance and security-related training. Other information resources include:

• ENISA: CSIRT Step-by-Step guide, 2006

• CPNI, United Kingdom: The WARP Toolbox

• GOVCERT.nl, The Netherlands: CSIRT in a Box

• Clearing House for Incident Handling Tools (CHIHT) resources (includes a listing of incident handling tools).

3.4. Global framework for watch, warning and incident response[4]

Many countries acknowledge the importance of an international framework for cooperation and collaboration in addressing misuses of cyberspace. Effective national watch, warning, and incident response capabilities are essential for investigation and collection of evidence relating to cybercrimes for effective prosecution and law enforcement. Principles of mutual assistance and partnership are vital for law enforcement authorities to cooperate to build confidence and security in ICTs. A global framework is also needed to ensure cross-border coordination between new and existing initiatives, and to help improve coordination at the regional and international levels. Chapter 5 “International Cooperation”, describes international cooperation and a global framework for cybersecurity.

The cyberthreat environment evolves very rapidly and is very complex and difficult to understand. This makes collaboration between CERTs vital and irreplaceable. CSIRTs need to keep abreast of developments in new cyberthreats and how best to deal with them. CSIRTs need to cooperate to be effective.. Cross-border mechanisms for information-sharing are essential for managing crises and mitigating potential damage in case of large-scale or cross-border cyber-incidents.

A number of Watch and Warn Networks (WWN) currently exist - within firms, sectors and national jurisdictions, as well as at the regional and international level. The efforts of these groups are critical to the success of any framework extending their coverage. The success of any WWN depends on trust and mutual assistance between operational incident handlers. A directory of these networks could be made available to ensure that they remain accessible. Stakeholders can also participate in international incident response communities and conferences (e.g., FIRST, CERT/CC or the Asia-Pacific Computer Emergency Response Team, APCERT) to increase awareness of the complex nature of cross-border collaboration, regulatory restrictions and operational/technical issues.

The “Forum of Incident Response and Security Teams” (FIRST) was established in 1990 and provides a meeting point for CSIRTs worldwide. It promotes active cooperation in incident response. Many teams working within private companies have joined FIRST, so its membership has now grown to some 200 members from five continents. Many members are now private companies, attracted by the opportunity of sharing in a body of knowledge otherwise difficult to access. Private and public partnerships can also help ensure that watch, warning and incident response capabilities are effective and efficient, by capitalizing on private sector expertise in incident response. Other regional forums and bodies promoting cooperation among CSIRTs include the European Government CERTs group (EGC), NORDUnet, CEENet and APCERT (an offshoot of the Asian Pacific Economic Cooperation or APEC).

3.5.1. Building Referential

The ISO 27000 family standards could be adapted and used for organizational structures in a national cybersecurity programme. This standard establishes “guidelines and general principles for initiating, implementing, maintaining, and improving information security management within an organization”. The controls listed in the standard are intended to address the specific requirements identified by a formal risk assessment. The standard is also intended to provide guidance on the development of “organizational security standards and effective security management practices and to help build confidence in inter-organizational activities”. It may be applied to the development and publication of industry-specific versions. ISO 27002-2005 covers:

• Structure;

• Risk Assessment and Treatment;

• Security Policy;

• Organization of Information Security;

• Asset Management;

• Human Resources Security;

• Physical Security;

• Communications and Operations Management;

• Access Control;

• Information Systems Acquisition, Development, Maintenance;

• Information Security Incident management;

• Business Continuity; and

• Compliance.

3.5.2. NCSec Referential

Based on ISO/IEC 27002-2005, the national cybersecurity standard (NCSec Referential) can help countries respond to specify cybersecurity requirements. This referential is split into five domains:

1. NCSec Strategy and Policies;

2. NCSec Organizational Structures;

3. NCSec Implementation;

4. National Coordination;

5. Cybersecurity Awareness Activities.

It also proposes 34 control objectives comprising a generic functional requirements specification for a country’s information security management architecture:

1. NCSec Strategy and Policies

1.1 Persuade national leaders in the government of the need for national cybersecurity;

1.2 Promulgate and endorse a National Cybersecurity Strategy;

1.3 Identify a lead institution for developing a national strategy;

1.4 Identify lead institutions for each element of the national framework;

1.5 Identify elements of government with interest in cybersecurity;

1.6 Identify policy development of a national strategy for cybersecurity;

1.7 Define mechanisms that can be used to coordinate the cybersecurity activities;

1.8 Ensure that a lawful framework is settled and regularly levelled;

1.9 Assess periodically, the current state of cybersecurity efforts and define priorities.

2. NCSec Organizational Structures

2.1 Identify National Cybersecurity Council for coordination between stakeholders;

2.2 Define Specific high level Authority for coordination among cybersecurity stakeholders;

2.3 Establish a national CERT to prepare for, detect, respond to and recover from national cyber-incidents;

2.4 Encourage development of sectoral CERT or CSIRT;

2.5 Establish points of contact within government, industry and university to facilitate consultation, cooperation and information exchange with national CERT.

3. NCSec Implementation

3.1 Identify lead institution for coordinating ongoing national efforts and mechanisms for coordination;

3.2 Identify mechanisms for coordination among the lead institution and other participants;

3.3 Establish or identify a computer security incident response team with national responsibility (N-CERT);

3.4 Identify the appropriate experts and policy-makers within government, private sector and university;

3.5 Identify institutions with cybersecurity responsibilities for sharing of policy and technical information and the prevention, preparation, response, and recovery from an incident.

3.6 Establish an integrated risk management process for identifying and prioritizing protective efforts regarding cybersecurity, particularly Critical Information Infrastructures.

4. National Coordination

4.1 Identify cooperative arrangements for and among all participants;

4.2 Establish mechanisms for cooperation among government, private sector entities, university and Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) at the national level.

4.3 Identify international expert counterparts and foster international efforts to address cybersecurity issues, including information sharing and assistance efforts;

4.4 Identify training requirements and how to achieve them;

4.5 Encourage cooperation among groups from interdependent industries;

4.6 Establish cooperative arrangements between government and private sector for incident management.

5. Cybersecurity Awareness Activities

5.1 Implement a cybersecurity plan for government-operated systems;

5.2 Implement security awareness programs and initiatives for users of systems and networks.

5.3 Encourage the development of a culture of security in business enterprises;

5.4 Support outreach to civil society with special attention to the needs of children and individual users.

5.5 Promote a comprehensive national awareness program so that all participants—businesses, the general workforce, and the general population—secure their own parts of cyberspace;

5.6 Enhance Science and Technology (S&T) and Research and Development (R&D) activities.

5.7 Review existing privacy regime and update it to the online environment;

5.8 Develop awareness of cyber risks and available solutions.

Cybersecurity is a global issue, needing a global approach to mitigate the growing ICT-related risks and cyber-threats. To be effective, international cooperation to promote cybersecurity must be built on sound national institutions and organizational structures. National strategies to promote cybersecurity have to take account of the different stakeholders and existing initiatives. Countries should adopt a multi-stakeholder approach, as the public or private sector alone cannot secure cyberspace. An approach based on dialogue, partnership and broad participation will benefit all stakeholders.

Specific actions are needed at the national level to build cybersecurity capacity in order to be able to respond to national and international incidents and misuses of ICTs. Awareness campaigns should be undertaken to educate and train all the actors of the information society, from decision-makers to citizens, including children and older people. However, awareness alone is not sufficient to empower end-users to adopt safe behaviour online. At the same time, efficient, simple and cost-effective security measures have to be undertaken.

With its Global Cybersecurity Agenda, ITU has established a unique framework to deal with global challenges to building confidence and security in the use of ICTs. ITU has developed an innovative and efficient interdisciplinary framework from which effective strategies can be developed by leading experts to build an inclusive and secure information society.

“Computer Security Incident Response Teams: An Overview” by Benoit Morel, David Mundie & Adam Tagart, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh.

NCSEC Referential and the ISO 27000 family standards

[1] This Section draws substantially on “Computer Security Incident Response Teams: An Overview” by Benoit Morel, David Mundie & Adam Tagart, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, published by ITU and available from ITU’s website, which provides a comprehensive overview of the development of CERTs/CSIRTs.

[2] The terms CERT and CSIRT are used synonymously. “CERT” was the name given to the original group at the Software Engineering Institute (SEI). As concerns over IT security grew, similar teams were established in the U.S. and abroad, which were also called CERTs. SEI then sought and was awarded a trademark for the term “CERT”. Security teams that wish to use the acronym CERT must first apply to SEI for permission. The question of what to call security teams who have not applied for the use of the term “CERT” was resolved by the term “CSIRT”. People often use “CERT” as a generic term and have tried to find semantic differences between the two names, where there are none - many CERTs tend to be older and larger than average, but that is mainly due to the fact that these centres have grown to a size where having the term “CERT” in their title is worth the effort of applying for permission to use it.

[3] “National Computer Security Incidents Response Teams”, published by SEI/CERT, 2007.

[4] Some material in this Section is drawn from “Computer Security Incident Response Teams: An Overview” by Benoit Morel, David Mundie & Adam Tagart, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, published by ITU and available from ITU’s website, which provides a comprehensive overview of the development of CERTs/CSIRTs.