|

|

IET Archives |

|

|

Alexander Bain (1811–1877) |

Pictures via a pendulum

The invention of the fax machine

Sending images through telephone lines to be reconstructed at the

receiver’s end as a facsimile of the original — or fax — is nowadays being

overtaken by other forms of electronic communication. But remotely printed paper

messages still have many uses, and have done for more than 150 years. It might

surprise you to know that the fax machine was invented decades before the

telephone.

|

Marius Rensen |

|

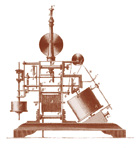

Illustration of Bain’s machine in 1850 |

The Scottish shepherd

Sending a message by wire became possible with the start of telegraphy. But

what about the amazing prospect of sending a signature or picture? In answer to

the question in last month’s Pioneers’ Page, this technique was first

demonstrated in the 1840s by a Scotsman, Alexander Bain.

Bain was born in 1811 in Caithness, in the far north of Scotland, one of

13 children of a crofter. As a boy, he helped to look after the sheep, but on

leaving home he trained as a clockmaker, eventually moving to London in 1837 to

pursue his trade. As well as mechanical devices, Bain was fascinated by

electricity. In 1841, he patented the world’s first electric clock, which worked

with a pendulum moved by electromagnetic impulses; this was to be an important

step on the road towards the fax machine, which became Bain’s next invention.

|

In 1902, Arthur Korn, of Germany, demonstrated the first photoelectric fax system, and in 1922 one based on radio signals. Faxes became widely used for transmitting newspaper content and weather maps. ITU played an important role by approving the fi rst international standards for fax machines (Group 1) in 1968, followed by Group 2 standards in 1972 and Group 3 in 1980. The time needed to transmit a page was reduced from six minutes to less than one, and the standards were essential factors behind the boom in fax technology of the 1980s. |

A vital element of his "recording telegraph" was synchronization of the

pendulums of two clocks which, for the scientist’s initial experiments, were

about 70 kilometres apart in Edinburgh and Glasgow. Whenever the Edinburgh

pendulum moved, a pulse of electricity went along a telegraph wire to a solenoid

on the Glasgow pendulum that moved it simultaneously. Attached to each pendulum

was a metal stylus. At Edinburgh, this swept backwards and forwards across a

picture etched in copper (or, later, printer’s type), and when it met a line in

the drawing an electrical contact was made. The signal made the Glasgow pendulum

move across paper soaked in potassium iodide, which changes colour when an

electrical current passes through it.

Scanning line-by-line

A crucial feature of the recording telegraph was its use of scanning. The

copper picture that was being transmitted was moved along by tiny amounts with

each sweep of the pendulum; at the receiving end, the sensitive paper was on a

roll that advanced with each stroke. Thus, a facsimile image was gradually

constructed, line by line.

Bain was granted a British patent on his device in 1843. His invention was

later improved by another Briton, Frederick Bakewell, whose system used

revolving drums covered with tin foil. The image was drawn onto the transmitting

drum with a non-conductive material. The drum was then scanned, while at the

receiving end, an image was produced on chemically treated paper wrapped around

the second drum. Bakewell gave the first public demonstration of a fax

transmission in 1851 at the Great Exhibition in London.

The Italian priest

Despite these successes, it remained a problem to achieve perfect

synchronization of the transmitting and receiving ends of the first fax systems.

The challenge was taken up by an Italian priest, Giovanni Caselli (1815–1891),

who researched into the telegraphic transmission of images while teaching

physics at the University of Florence. In 1860, working in Paris, he built a

machine that he named a "pantelegraph". Essentially a giant, 2-metre-tall

version of the earlier devices, it overcame the synchronization problem by

triggering pendulum movements with extremely accurate clocks that operated

independently of the electric current sent down the telegraph line.

|

|

Marius Rensen |

|

Caselli’s pantelegraph

|

|

Alex de Carvalho |

|

Giovanni Caselli was reportedly given the task of

constructing the famous pendulum of French physicist J.B. Léon Foucault, which

was used to demonstrate the rotation of the Earth |

The pantelegraph was widely acclaimed, and France’s Emperor Napoleon III gave

it his backing. Caselli was allowed to use a telegraph line between Paris and

Amiens to test the device, which he patented in 1861. A commercial fax service

was started in 1863 between Paris and Marseille, followed in 1865 by one between

Paris and Lyon. Thousands of faxes were now being sent across France by

pantelegraph.

However, the pantelegraph failed to become a long-term success. It was not

promoted well enough, and more simple forms of telegraphic transmission

ultimately prevailed. It serves as an example of a technology that did not find

a niche because it was ahead of its time. Nevertheless, four years before the

birth in Scotland of Alexander Graham Bell who patented the telephone, Scotsman

Alexander Bain had arrived at the concept of image scanning that was to be the

basis of not only the fax technology of the future, but also of a fundamental

technique of television.

| |

Question for next time

Printing words mechanically was another way to send writing by telegraph. In

what year was the typewriter first patented?

|

|

|