C. M. Armstrong during the opening of the Policy and Regulatory Summit of the Forum of Telecom 99

(ITU 990102)

New technology and new competition are redefining what is possible in telecommunications. They are doing so with a speed that would have been unthinkable just a few years ago. For sheer speed of popular acceptance, wireless technology is the only application that rivals the Internet. And now the stage is set to combine those two applications. You can see it in the phenomenal growth of digital wireless. Worldwide there are an estimated 220 million digital wireless subscribers, and that number is headed towards one billion in just five years.

The telecommunication industry today offers options to customers and benefits to society beyond the scale of anything we have seen before. The communications revolution has begun, and there is no turning back.

This can be the first revolution in history that has no losers. Everyone stands to benefit. But there is important work ahead.

Let us jump ahead a hundred years and ask two questions.

The first is, during the 21st century, did communications technology deliver real progress for people around the world?

The answer will be "yes".

But question number two is a little more complicated. Did that progress come quickly and efficiently because regulators and the industry did everything possible to accelerate it, or was it slow and fragmented because we stubbornly clung to the side of the 20th century regulatory mo-del, even though that ship was obviously sinking?

We all want to see the benefits of the communications revolution delivered with speed and efficiency to all regions of the world. To make that happen, industry and the regulatory community have a joint responsibility to keep the flywheel of competition and technology turning.

As you know, a flywheel is the large wheel inside an internal combustion engine that keeps the power flowing smoothly. The flywheel that drives the communications revolution is moved by the forces of competition and technology.

New technology generates new competition. New competition in turn generates new technology. That is the way it is supposed to work in a free market.

In the communications market, the industry has to supply the technology and the competition. But public policy has to create the environment where the flywheel can keep turning smoothly — an environment where new technology and new competition can enter the market without obstruction. That is a critical responsibility. But once the environment for competition is created, regulators must have the self-restraint to keep their hands off the flywheel. The focus of the regulation must change.

The days of preserving artificial markets through regulatory restrictions should be long gone. In today's communications market, the job of the regulator is to let market forces work, while protecting the public interest. The faster the flywheel of competition and technology turns, the faster the public receives the benefits.

The faster the flywheel of competition and technology turns, the faster the public receives the benefits

With those dynamics in mind, let us address a three-point call to action for the telecommunication industry:

Each of these three action points has far-reaching implications for this industry and global society.

In some parts of the world, competition and new technology are creating new markets, launching new companies, inspiring entrepreneurs, causing some market leaders to team up with new partners and attracting record investment.

There is no shortage of venture capitalists ready to invest in telecommunication infrastructure and services, from Berlin to Bangkok, from Basking Ridge to Britain. The five biggest merger and acquisition deals in the history of world commerce were all made in 1998. Three of them involved telecommunication companies. As it happened, all of the companies were American, including AT&T. These three deals alone were worth almost USD 214 billion.

One day Delora Begum got a USD 350 development loan and invested it in a cellular phone, the first phone of any kind in her village

But telecommunication investments are not just financial engineering. They bring real benefits to real people; sometimes in countries where those benefits have been a long time coming.

Consider the little village of Chandryel in rural Bangladesh. Until recently, anybody there who wanted to make a phone call had to travel 8 km to the closest regular payphone which often did not work. But then Delora Begum got a USD 350 development loan and invested it in a cellular phone, the first phone of any kind in the village.

The broadband design of the cable connections is also an ideal way to deliver advanced digital services

(ITU 990103)

Now the people of Chandryel come to Ms Begum's hut. For a reasonable fee, her phone connects them to the rest of the world. Village farmers can call the capital to check on grain prices. Medical help is a phone call away. For the first time, a mother in Chandryel can talk to her emigrant son who just happens to drive a cab in New York.

This is all possible because a non-profit lending institution in Bangladesh teamed up with the Norwegian phone company Telenor to build a rural wireless network. They sell air time to people like Ms Begum who is known in her village as "the phone lady".

Like most developing nations, Bangladesh still has a long road to travel in terms of creating telecommunication infrastructure as well as a competitive market. But the phone lady represents one small pocket of progress. There is much more coming.

Of course, progress is driven by investment. And investment goes fastest to those countries with an open telecommunication market. A market where new competitors can invest and have a fighting chance to win a return. That is why the WTO Basic Telecommunications Agreement needs all the support ITU can provide.

About 80 countries have formally ratified the agreement. They represent 90 per cent of the world's telecommunications traffic — but less than half of ITU's membership.

We need to encourage a commitment by those countries that have not yet made one. Equally important, those countries who have already ratified need to remember this was just a first step.

Now it is time to accelerate implementation. No market was ever opened through just good intentions alone. The transition from regulated monopoly to competitive market is a tough one, and not just in the developing world.

In theory, the fastest way to introduce competition is to give new competitors access to the incumbent monopoly company's network through unbundled network elements or the resale of the incumbent's services at discounted wholesale prices.

That is what got real competition started in the United States long-distance market back in the 1970s and early 1980s. Regulators required AT&T to sell network capacity to new competitors at rational discounts. That created a thriving resale market almost immediately.

This opportunity for viable market entry, in turn, gave new competitors the experience, capital and market presence they needed to begin to deploy their own facilities.

But we have had mixed results with the resale option in the United States local services market. A market liberalization act passed by the United States Congress in 1996 was supposed to open up that market. But the big regional monopolies that control local phone service have been very slow to grant access to their local networks. The wholesale discounts they have offered so far have been minimal so that resale is often not an economically viable option.

AT&T is one of the new competitors in local service. We have made substantial investment in cable television companies to give us direct access to customers over our own local facilities. The broadband design of those cable connections is also an ideal way to deliver advanced digital services.

But no new competitor can hope to reach every household in the United States or any other country for that matter. Access to incumbent companies' networks and economically viable resale of their services are still crucial to creating open markets, anywhere in the world.

Now let me go from open markets to a market that is already wide open — Internet services. The public policy message here is deceptively simple. If ever there was an area for minimal regulation and reliance on market principles, this is it.

Internet services are the classic example of a 21st century technology and market changing too fast for regulation to keep pace. The market-place governs itself more efficiently and more quickly than any government agency ever could.

Internet services are the classic example of a 21st century technology and market changing too fast for regulation to keep pace

But the government does have a critical role. First, it needs to preserve, protect, and promote competition. Second, the government should encourage self-regulation and self-policing by the Internet industry, and on a global scale. That way we can avoid a patchwork of national regulations with no consistency.

That kind of nation-by-nation regulation is anathema to the Internet, because the Internet is a truly global medium, and electronic commerce knows no boundaries. Regulators should turn their attention to global standards, the third and final point of my call for action.

We need global standards; and we need them quickly. ITU has a rich history in setting standards for interconnection and operation. But we all realize the traditional approach to standard setting that worked well through the 19th and 20th centuries just will not get the job done in the 21st.

Negotiating interconnection standards from a patchwork of national standards was a major contribution. But the speed of 21st century technology does not allow for that. A new service can be obsolete by the time standards are agreed to.

We need true global standards, deployed quickly, in cooperation between the industry and ITU. The alternative is a series of competing proprietary standards. Because the market will not wait for anybody when it is ready with a new offer.

The progress towards a third generation global wireless standard is encouraging. ITU has brought the major players together. The industry competitors are proposing specific standards. ITU is rationalizing them in the public interest. I am sure we will see more progress like that on global standards in the future. Like everything else in today's telecommunication industry, speed is critical.

I assure you AT&T will cooperate in every way possible to see those three action points realized. Our actions in the market-place will reflect our convictions.

The global venture we are launching with BT is certainly a case in point. Like any business venture, this one is designed to provide better service for its customers and economic growth for both companies and their shareholders.

But the AT&T/BT joint venture reflects our belief in the future of an open, competitive global telecommunication market. We are not only investing our hopes in that kind of market, we are investing our resources as well.

Like so many other companies in this unique and wonderful industry, we look forward to a future where a continuing flow of new competition and new technology will keep the flywheel turning.

We also look forward to continuing our long and productive relationship with ITU. We respect this organization's continuing efforts to keep its mission relevant to the needs of this fast-changing market.

Erkki Liikanen during the Forum opening (Telecom 99)

(ITU 990115)

We are witnesses of, and actors in, the transition from an industrial society, based on mass production, towards an information society, which is characterized by globalization and mobility.

There are different ways to describe this new economy: the digital economy, the network economy, the information-based economy. Digital technologies and global communication networks are transforming economic activities, bringing about increased productivity, new opportunities and new jobs — and this is true for both developing and developed countries. But only as long as the policy framework enables industry to exploit these opportunities.

It is on this policy framework that I would like to elaborate further.

Liberalization in the European Union (EU) started in 1987. That now seems like ancient history. Who could have foreseen the impact that the Internet has had? The Internet has been a catalyst for the creation of a global electronic market-place.

This year about 150 million people in the world use the Internet. Next year this figure will approach 200 million. And soon many more will be somehow connected: via a computer, a set-top box or a mobile device.

A similar dynamic development is characteristic for mobile communications: in the early 1990s the European Commission estimated that at the end of the decade there would be about 40 million subscribers. This was considered as a very optimistic forecast. The reality is astonishing. We have today 120 million mobile subscribers in the EU. And many expect the penetration rate to go even close to 100 per cent within the next five years.

GSM has become a global standard, used by over 300 operators in 130 countries. We expect third generation mobile telephony to build on this success. I am encouraged that as a result of the IMT-2000 process, a global solution to third generation looks likely.

This would be a massive achievement, with major economic benefits, especially since it is forecast that worldwide there will be over 600 million mobile phones with e-commerce capabilities by 2004.

So far, it is undeniably the developed world that has reaped the most benefit from this revolution. But I do not believe that this is set in stone. The information society cannot, and must not, be a club for the developed world.

It is rare for issues to arise where social justice and economic reality go hand in hand. I believe this is the case for the information society. All countries will have to liberalize their telecommunication networks in the end. This is unavoidable. Those that fight against it often do so in the name of social justice. They argue that liberalization will reduce economic and social cohesion. The rich will get richer and the poor will be poorer. However, there is no inherent conflict between liberalization and social justice in the field of the information society.

Economic and technological developments in this area empower all sections of society. Innovation is bringing down the cost of access to information, to new technologies and services. The developed world was the "early adopter" — but who is to say that other parts of the world cannot use this technology to outstrip the developed world?

There are many issues to face. For instance, in ITU, there are discussions ahead on the future of the accounting rate system. These will not be easy. But we must reach an agreement.

Developing countries themselves need to put in place the necessary institutional and legal framework for liberalization. I know from the EU experience that this takes time, and resources. The EU will do its utmost to help developing countries to adapt to the new telecommunications landscape. We will support the development of the necessary regulatory culture to facilitate liberalization with cooperation instruments and financial support.

The opportunities of the information society are available to all countries. However, if you want the benefits, you have to seize them. Do not expect the benefits of the information society without being ready to adopt the appropriate policy response.

The EU liberalization has been successful, but much remains to be done, particularly in three key areas.

Let us have a look at some of the problems involved. A good example is licensing. Licensing can work as an obstacle for the development of competition as it can block market entry. Today we have a situation where authorization regimes differ, so that the same operator must adapt its request for authorization to fifteen different regimes.

In some Member States, an operator can start providing services immediately. In others the operator must seek an individual licence from the regulator. The conditions attached to these licences vary.

The opportunities of the information society are available to all countries, and if they want the benefits, they

have to seize them

Photo taken in Viet Nam, Jean-Marie Micaud (ITU 990086)

Such differences constitute obstacles for the activities of pan-European service providers such as satellite operators. This is one reason why most operators remain focused on operating nationally, rather than seeking to pursue pan-European business strategies.

In some cases the regulatory regime is conditioning how an operator provides the service. This cannot be right: the tail is wagging the dog. We need to reduce the red tape so that operators are free to innovate. We need to make changes to the framework to encourage more effective competition. And we need to do this while continuing to protect consumers and to guarantee a minimum level of service to the disadvantaged in society.

The European Commission was to issue, late in October 1999, a policy document suggesting policy orientations to address the shortcomings. We want to hear the views of national authorities, market players and other interested parties. In the light of their reactions, we will make proposals for a new regulatory framework.

So far, only 75 countries have made commitments to the WTO Basic Telecommunications Agreement signed in 1997. We hope that the other hundred ITU Members will join soon

The EU has welcomed global competition. There is no more open market of comparable size in the world than the EU. If we are to achieve the aim of effective competition and a first-rate communications infrastructure, open market is essential. With the regulatory review, the markets will be even more open.

We encourage also others to open their markets. An open and competitive global telecommunications market is in the interest of every country. The quality of communications infrastructure is a key determinant of foreign investment. Only liberalization can deliver this.

The World Trade Organization's General Agreement on Trade in Services (WTO/GATS) has made substantial progress towards this end. But as in the EU, more needs to be done. Therefore, through the WTO/GATS Millennium Round in telecommunications, the European Commission would like to obtain more and better commitments from WTO members; a proper implementation of commitments and the implementation of a transparent and predictable regulatory environment to make the rules work.

We also want to see the scale of the telecommunications agreement expanded. So far, only 75 countries have made commitments to the WTO Basic Telecommunications Agreement signed in 1997. We hope that the other hundred ITU Members will join soon.

A major challenge for policy-makers is to take account of rapid technological change in the communications sector. Available computing power is doubling every eighteen months and transmission capacity every twelve months. We should not be surprised that current rules are becoming harder to apply in the face of technological and market change.

For example, as voice over Internet develops, and major operators use IP networks to carry traffic, how relevant is the distinction between voice and data traffic? And as convergence between broadcasting and telecommunications intensifies, can we continue to justify different rules for these sectors?

With the rise of the Internet, we are confronted with a global market. Technological change has consequences for global regulation in the same way as it affects EU rules. We have to look again at global regulation in the light of evolution in technology and the market. But in the global context, do we have the right tools to meet this challenge? Are current institutions adequate for the task?

In the European Union we have a clear institutional and legal order, which makes it relatively easy to allocate tasks and responsibilities. It is for these reasons that the European Commission is able to carry out a regulatory review, which covers the whole range of community policy in the sector. Such a framework does not exist at global level. This is a fact. It is not going to change. Even if a global regulatory framework for the Internet were desirable, it would be impossible to create one.

There are issues that need to be managed at global level — for example allocation of radio spectrum. I pay tribute to the past efforts of ITU in this context. But convergence and the speed of technological development mean that ITU now faces the biggest challenge it has confronted in its long history. I welcome the actions proposed by ITU Secretary-General, Yoshio Utsumi, to respond to this challenge — and look forward to the report of the expert group, which will meet to discuss these issues. The EU will do its utmost to ensure its success.

But not all the relevant issues fall within the remit of ITU. Many different institutions have a role to play. We must ensure there is adequate flexibility and coordination between these institutions. We have to ensure that the international community responds quickly and in a coherent manner.

I have given you an outline of how the EU intends to respond to the challenges of the global information society. An open and competitive global market, a flexible, rapid and coordinated regulatory approach at global level — these are my policy prescriptions.

To achieve this, we still need to undertake courageous policy measures — in the EU, but also elsewhere. The objective should be to foster competition by making access to networks subject to transparent and non-discriminatory rules, by reducing regulatory red tape, and by opening up markets.

If we fail, we will lose the full benefit of the global information society — so essential to improve the quality of life of our citizens, and so essential for the health and wealth of our societies as a whole. This is a revolution — it therefore needs a strong policy response.

We are prepared to deliver this response.

On 14 October 1999, BT and Microsoft Corporation announced an agreement to combine efforts in developing mobile Internet and multimedia applications and equipment.

The worldwide agreement is expected to lead to new types of service with broad customer appeal.

The two companies will join forces to:

create a mobile multimedia service which allows customers to display and access personalized information on handheld wireless devices;

develop handheld interactive wireless devices based on the Microsoft Windows CE operating system;

establish an open industry forum for the development of third generation (3G) mobile Internet applications.

Both companies are to commit substantial resources to collaborative work in the belief that the market for mobile Internet and multimedia products and services represents a massive opportunity for rapid business growth, based on existing mobile networks as well as the forthcoming 3G networks, including the universal mobile telecommunications system (UMTS).

Sir Peter Bonfield, BT's Chief Executive, said: "By deepening our relationship with Microsoft we believe we can create world-class capabilities for our customers. Mobile access to the Internet is a fantastic growth market."

Bill Gates, Chairman and CEO of Microsoft, said: "Mobility is a key component of Microsoft's vision, and we are excited about working with a world-class network provider like BT to make that vision a reality. Microsoft's platforms and services combined with BT's mobile networks will enable users to access rich, interactive information anytime, anywhere and on any device."

The collaboration will give individual, personalized deliveries of Internet content and services to users of mobile telephones, laptop computers and a forthcoming new generation of interactive consumer devices. This capability will complement Project Nomad, an existing collaborative development programme between BT and Microsoft, which lets users of mobile phones read, send and receive e-mail and calendar information. Initial customer trials of these services were announced on 6 October 1999.

Users will be able to access rich, interactive information anytime, anywhere and on any device

BT will develop additional consumer products, including games, music and other interactive services.

The two companies will work together to build a new generation of mobile handsets and computing devices which will exploit fully the power of BT's mobile networks to deliver multimedia content and interactive games.

They will also find a forum for the development of 3G and general packet radio services (GPRS) mobile applications. This will be an open industry forum based on Internet standards to encourage development of new multimedia applications for mobile devices, and the conversion of existing applications to work in the wireless mobile environment.

The first products and services from the new agreement are expected to become available to customers in the year 2000. — BT.

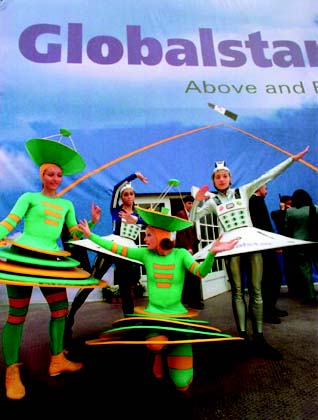

On 11 October 1999, Globalstar marked the official introduction of its mobile and fixed telephone service, which is poised to bring affordable, high-quality telephony service to virtually any place on Earth. The satellite-based telecommunications system is initiating service in phases in regions of the world covered by its first nine operational gateways, or ground stations.

The official roll-out of service is expected to begin region-by-region

Globalstar initially will provide limited distribution of service to selected individuals during "friendly user" trials in the United States, Canada, Brazil, Argentina, China, Republic of Korea, South Africa, and parts of Europe, allowing service providers to make final adjustments and refinements before launching full commercial service over the next few months. During this period, marketing, distribution and customer care systems in these locations will be tested and adjusted based on feedback from early users, assuring high quality service when Globalstar is more broadly introduced around the world in the coming months.

Call signals are received using simple handsets or fixed phones, which operate much like conventional cellular

or wireline phones

(ITU 990105)

Bernard L. Schwartz, Chairman and Chief Executive Officer of Globalstar, said: "Business people, residents of communities in developing countries, and industrial users in distant or offshore locations can now access mobile, affordable telecommunications wherever and whenever they need it. We have conducted exhaustive testing and placed more than a million phone calls over the system, ensuring highly reliable services with remarkable voice clarity."

Using simple handsets or fixed phones, which operate much like conventional cellular or wireline phones, Globalstar call signals are received by a constellation of low-Earth-orbiting satellites which cover virtually every populated area on Earth, routing calls back to Globalstar gateways, into the terrestrial phone network and on to their destinations. The system's patented CDMA (code division multiple access) technology not only increases system capacity but allows each call to be supported by multiple satellites simultaneously, a function available exclusively through Globalstar. Thus, if a caller moves out of range of a satellite, the call is seamlessly handed off to another.

Globalstar's multimode phones may be used in cellular or satellite mode. The phones automatically search for a terrestrial cellular connection where available but switch to satellite mode whenever the user is out of cellular range, effectively expanding the reach of the cellular network. While terrestrial cellular coverage continues to grow around the world, it is estimated that nearly 90 per cent of the Earth's surface remains unserved by a cellular network. These areas now will be covered by Globalstar service.

Fixed phone units are available for use in communities lacking cellular or wireline service, particularly in developing countries, and at remote business and industrial locations such as mines, petroleum exploration sites, and aboard ocean-going vessels.

Globalstar will also offer many of the functions and services familiar to regular cellular users, including call forwarding, voice mail, short messaging service (SMS), and later in the year 2000, data and fax capabilities.

Globalstar service will be available to subscribers through a worldwide network of established, telecommunication providers who are experienced at identifying local market needs and requirements. These include Vodafone AirTouch, TE.SA.M. (a joint venture between France Télécom and Alcatel), Dacom, Elsacom (a Finmeccanica company) and China Telecom.

Globalstar, led by founding partner Loral Space & Communications, is a partnership of many of the world's telecommunications service providers and equipment manufacturers. In addition to the service providers listed above, Globalstar partners include co-founder Qualcomm, along with Alenia Aerospazio (a Finmeccanica company), DaimlerChrysler Aerospace, and Hyundai.

If a caller moves out of range of a satellite, the call is seamlessly handed off to another (Symbolic

illustration at Telecom 99)

(ITU 990106)

Loral Space & Communications, qui est le partenaire gérant, détient une participation majoritaire (45% des parts) dans Globalstar. Loral est une compagnie de technologie de pointe qui s'occupe principalement de la fabrication de satellites et des services par satellite: location de répéteurs de radiodiffusion, services à valeur ajoutée, réseaux nationaux et internationaux de données d'entreprise, téléphonie hertzienne dans le monde entier, services de transmission de données à large bande et services de contenu, services Internet et services internationaux par satellite avec réception directe chez le particulier. — Globalstar.

Sadako Ogata during the session on "Telecommunications in the Service of Humanitarian Assistance" (TELECOM

99)

(ITU 990104)

Coming to Telecom 99 + Interactive 99 is an astonishing experience for a novice in telecommunications. Obviously, this is the showcase of a whole new world of opportunities — opportunities to get in touch, to learn, to know, to grow. These amazing achievements fill me with admiration.

Yet, I cannot help but think of many of the places where my colleagues of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) are struggling to protect and assist 22 million refugees and other uprooted people worldwide — dangerous and remote places, very cold, hot, or dusty; often without electricity; cut off from all networks — places where communication is hardly possible. I cannot help but think of the refugees themselves. Many of them have never used a phone in their life. Many others (and I do not know which is worse) had to leave behind them places in which they took easy communication for granted, like we do.

Refugees, of course, are not just victims — they are women and men able to make extraordinary contributions to society. Albert Einstein was a refugee. But refugees, in their vast majority, were either born, or were thrown, on the wrong side of the "digital divide".

Let me introduce UNHCR, the United Nations refugee agency. Our work started in December 1950. We were a small organization, with a staff of 23 and a yearly budget of less than USD 5 million.

Almost fifty years later, we employ over four thousand people. Our yearly budget, since 1992, has constantly exceeded USD 1 billion. Twenty years ago, we dealt with 2.5 million refugees. Today, the Office cares not only for 12 million refugees, but also for more than 10 million other people — such as persons displaced within their own country, returnees, and so on.

Increasingly, huge logistical means must be mobilized to bring assistance to uprooted people — many of you will remember the airlift which kept the city of Sarajevo alive for three years during the war in Bosnia; or another airlift, which brought emergency assistance to a cholera-stricken population of one million Rwandans in the Zairean (now Congolese) city of Goma. The images of the Kosovo refugee tragedy are still vivid in our minds. As we speak, my colleagues are facing another challenging and difficult time helping refugees in places such as East Timor, Burundi and the North Caucasus.

UNHCR's work is not simply "humanitarian". We deal, specifically, with refugees, returnees and other people who are either displaced, or trying to resume a normal life, at home or in another country. They are all people on the move, people separated from their children, parents and friends, deprived or traumatized people, people who therefore desperately need to communicate.

On the other hand, to ensure their protection and provide them with assistance, we must be with the refugees. This means that the staff of UNHCR and of its partner agencies must often work in remote, isolated places. Think of Sierra Leonean refugees in the Liberia rainforest, for example — one of the most inaccessible areas in the world. Think of the 150 000 internally displaced people in Afghanistan, a country in which simple telecommunication technology is as accessible as science fiction. These places are not just under-equipped, they are also dangerous, especially if you cannot communicate effectively.

Good, efficient, accessible telecommunications are therefore a key element of refugee operations. I would even go further and say that they are an essential tool to protect refugees and to provide security to staff working with them.

Just like any other human activity, humanitarian and refugee programmes today require professional and dedicated backing, including state-of-the-art support in the field of communications and information technology. One of the most typical features of today's refugee crises is (frequently) the size and speed of forced population movements. In these emergencies, UNHCR's traditional information, communication and refugee registration systems (designed for more manageable crises) have come under incredible strain.

The Kosovo crisis was a turning point. It attracted a lot of attention which included business companies eager to help us address the movements of enormous masses of people, first fleeing Kosovo, and shortly thereafter returning home. Thanks to BT, in some locations, refugees were able to call, free of charge, their relatives in other countries. This helped family reunification and was of great psychological help. Thanks to the European Telecommunications Satellite Organization (EUTELSAT), we are continuing our efforts to improve communications in Kosovo today. Thanks to a very substantial contribution of resources by Microsoft Corporation and several computer companies, we tried a new, electronic refugee registration package, which we hope to improve and use in other situations as well. This is particularly important.

The staff of UNHCR and of its partner agencies often work in remote, isolated places

Source: UNHCR/ I. Guest (ITU 970164)

In many places we still register refugees by hand. Given the importance of registration to ensure fair food distributions, for example, or for the purpose of tracing lost relatives, we need to make fast progress in this field.

Many field officers, responsible for what are literally refugee cities, still rely on old-fashioned walkie-talkies

There are other areas in which we must improve our technology. For example, in carrying out campaigns to inform refugees about conditions in their own country, in order to help them make up their mind about staying where they are, or returning home. Our delivery of messages to large groups of people under difficult circumstances could improve immensely if we had more effective tools. I do not even need to mention the security of staff — many field officers, responsible for what are literally refugee cities, still rely on old-fashioned walkie-talkies.

Emergency teams setting up vast operations depend on a couple of satellite phones, and a few overworked technicians and operators. Yet, effective communication systems are crucial. We are more aware than anybody else of the importance of good telecommunications for security. However, limited resources mean that our access to the best technology is also limited.

Telecommunications today are about partnerships. Few other fields of business are so dynamic in searching for synergies, and in maximizing them. I represent here a very different world, in which partnerships are nevertheless as essential. I am here not only to tell you who we are, and what we do — but also to propose that you be partners in our endeavours to help people have better, safer lives. The challenges are immense.

Advanced technology will be crucial to strengthen our communication capacity, especially in chaotic emergencies — between our various offices, with our partner agencies, with the outside world, and — last but not least — with refugees.

I will be very practical and give you some examples:

I do not wish, however, to talk about partnership and then just give you a shopping list. We at UNHCR, and in the humanitarian community at large, are quite serious about working with you. I say so not only because we need your resources and know-how, but also because I sincerely believe that business — the telecommunications business in particular — has much to gain in being associated with humanitarian operations.

UNHCR is prepared to enter into stand-by arrangements with telecommunication companies, that could be activated in case of large emergencies, and through which resources can be made available, and more importantly, staff can be deployed to provide support in refugee operations. We are ready — through our offices in countries where your companies are based — to talk with you on how we can make telecommunications be of real service to refugee programmes.

To paraphrase Thomas Friedman, refugees are among the people who must still upload, rather than download, for a living. Although they very much need to communicate, they are also among the people who have the least means to do so.

You can help us link them up, so they will have a voice in the global world.

On 5 October 1999, MCI WorldCom* and Sprint** announced that the boards of directors of both companies had approved a definitive merger agreement to create a pre-eminent global communications company for the 21st century. The combined company, to be called "WorldCom", will provide a range of services to residential and business customers on its end-to-end network infrastructure. WorldCom plans to be at the forefront of the fastest growing areas of global communication services, offering innovative broadband, "all distance" services to businesses and homes, and nationwide digital wireless voice and data services.

The total value of the transaction is approximately USD 129 billion

The actual number of shares of MCI WorldCom common stock to be exchanged for each Sprint share will be determined based on the average trading prices prior to the closing of the deal, but will not be less than 0.9400 of a share (if MCI WorldCom's average stock price exceeds USD 80.85) or more than 1.2228 shares (if MCI WorldCom's average stock price is less than USD 62.15).

The total value of the transaction is approximately USD 129 billion (115 billion in equity and 14 billion in debt and preferred stock). The merger will be tax-free to shareholders and accounted for as a purchase.

The transaction is expected to be essentially non-dilutive to WorldCom's earnings per share before goodwill amortization ("cash earnings"). The combination should create significant cost savings that will allow the new company to compete aggressively in both the business and consumer markets and to invest in new technologies, such as broadband access and next generation wireless.

Both companies estimate that annual cash operating cost savings of USD 1.9 billion can be achieved in 2001 (the first full year of operation), increasing to 3 billion annually by 2004. These cost savings are anticipated to result from better utilization of the combined networks and other operational savings. Capital expenditure savings of 1.3 billion a year are expected in 2001 and beyond, primarily as a result of economies of scale and procurement efficiencies.

|

* MCI WorldCom is a global communications company with 1998 revenues of more than USD 30 billion and established operations in more than 65 countries encompassing the Americas, Europe and the Asia-Pacific regions. It provides facilities-based and integrated local, long-distance, international and Internet services. Its global networks, including its pan-European network and transoceanic cable systems, provide end-to-end high-capacity connectivity to more than 40 000 buildings worldwide. ** Sprint is also a global communications company which provides integrated long-distance, local and wireless communication services. Sprint built and operates the United States' first nationwide all-digital, fibre-optic network and is a leader in advanced data communication services. Sprint has USD 17 billion in annual revenues and serves more than 20 million business and residential customers. |

In particular the merger is expected to:

Bernard J. Ebbers, President and Chief Executive Officer of MCI WorldCom, said: "The economics of the combination are particularly compelling and WorldCom will have the capital, proven marketing strength and state-of-the-art networks to compete more effectively against the incumbent carriers domestically and abroad. The merger with Sprint is particularly timely as wireless communications emerges as a critical component of full service offerings. Increasingly, wireless will be used for Internet access and data services, two areas in which both companies excel. Gaining an all-digital nationwide footprint with common technology and spectrum that delivers next generation capabilities is of paramount importance."

The merger is subject to the approvals of MCI WorldCom and Sprint stockholders as well as approvals from the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) of the United States, the Justice Department, various State government bodies and foreign antitrust authorities...

William T. Esrey, Chairman and Chief Executive Officer of Sprint, said: "From building the first nationwide fibre-optic network to creating the nation's first all-digital, nationwide PCS wireless system, Sprint has been a pioneer in the communications industry. Sprint has utilized technology and marketing innovation to deliver value to consumers and businesses worldwide. Sprint will enable the merged company to provide end-to-end integrated broadband services for the home, as well as for the business market, as an alternative to traditional cable and telephony providers. The combined strengths of WorldCom and Sprint will allow us to bring customers a suite of fully integrated broadband and wireless all-distance services providing consumers and businesses with exciting competitive alternatives."

The merged company will be led by a management team of top executives from MCI WorldCom and Sprint. Upon completion of the merger, Mr Esrey will become Chairman of WorldCom. Mr Ebbers will be President and Chief Executive Officer of the combined company. The board of directors of the combined company will have 16 members, ten from MCI WorldCom and six from Sprint.

... D'après les prévisions des deux compagnies, la fusion devrait être achevée au cours du deuxième semestre de l'an 2000

The merger is subject to the approvals of MCI WorldCom and Sprint stockholders as well as approvals from the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) of the United States, the Justice Department, various State government bodies and foreign antitrust authorities. The companies anticipate that the merger will close in the second half of 2000. — MCI WorldCom/Sprint.

The European Commission has approved the acquisition of joint control by the Swedish and Norwegian Governments of a new company created to hold the shares of Telia AB (Sweden) and Telenor AS (Norway). This decision follows far-reaching commitments to open up access to the local access networks for telephony as well as to divest Telia and Telenor's respective cable-television businesses and other overlapping business. This is the first case under the European Commission Merger Regulation which involves the merger of two incumbent European Union (EU) telecommunication operators.

The Saurdalseggi transmitter on the west coast of Norway

Norwegian Telecommunications Administration (ITU 870129)

The European competition Commissioner, Mario Monti, stated: "Overall, I am satisfied that this decision suitably closes a complicated case. But this is a fast evolving industry and I am convinced that we will see further consolidation in the future. This is unlikely to be the last time that we will require cable-television network divestitures and/or local loop unbundling to resolve competition issues."

The merger concerns a number of different markets. Both Telia and Telenor are active across the full range of telephony and related services as well as in retail distribution of television services and related markets. Following an in-depth analysis, the European Commission concluded that the concentration as originally notified would have caused serious competition concerns by strengthening dominant positions in:

In order to address these concerns, Telia and Telenor were committed to the following:

The Swedish and Norwegian Governments have, in their capacity as owners, provided support for the undertakings.

Local loop unbundling will open up access to final users of telecommunication services in both Sweden and Norway and thus ensure that the merged entity will not be the only company having such access across those two countries, and the Nordic region

This decision is important in setting out the European Commission's approach to operations between incumbent operators in the EU. The European Commission will have a very close look at access to local telecommunications and cable-television networks when assessing any future notifications of mergers or joint ventures between those incumbent operators. It may be the case that the European Commission will again require cable-television network divestitures and/or LLU in future cases in order to resolve competition issues. This policy is consistent with the line taken in the Cable Review in 1998, where legal separation at the minimum was required between cable-television networks and telecommunication networks owned by the same incumbent operator. Further measures, including divestitures, were envisaged on a case-by-case basis, as has been the case with Telia and Telenor.

From a procedural viewpoint, the European Commission has accepted that the notifying companies faced additional and exceptional constraints in submitting the proposed commitments, due to the fact that, inter alia, their original merger plan had been approved by the Swedish and Norwegian Parliaments. The European Commission has therefore, exceptionally, agreed to take the proposed commitments into account.

It further took note of the clear-cut character of the proposed undertakings, which has enabled it to conduct a full and proper assessment of the modified proposal, including adequate consultation with EU Member States and third parties. — European Commission.